If it didn’t happen to be true, you might dismiss it as feel-good fantasy. But part of what makes The Greatest Game Ever Played so appealing is that this is a real-life Cinderella story tailor-made for classic drama.

Based on the 2002 book by Mark Frost (who also wrote the screenplay adaptation), the film details how a 20-year-old amateur golfer, Francis Ouimet, defeated the most celebrated pro golfer of his day, Harry Vardon, to win the 1913 U.S Open.

We are introduced to Francis as a boy growing up in a home just across the street from the Brookline, Mass., country club. A caddie at the affluent golf club, Francis spends his free time honing his putting and assiduously following the career of British golfing legend Vardon (Stephen Dillane). When the pro makes a promotional appearance in a Boston department store, young Francis shows up to marvel at his hero and winds up getting a quick lesson.

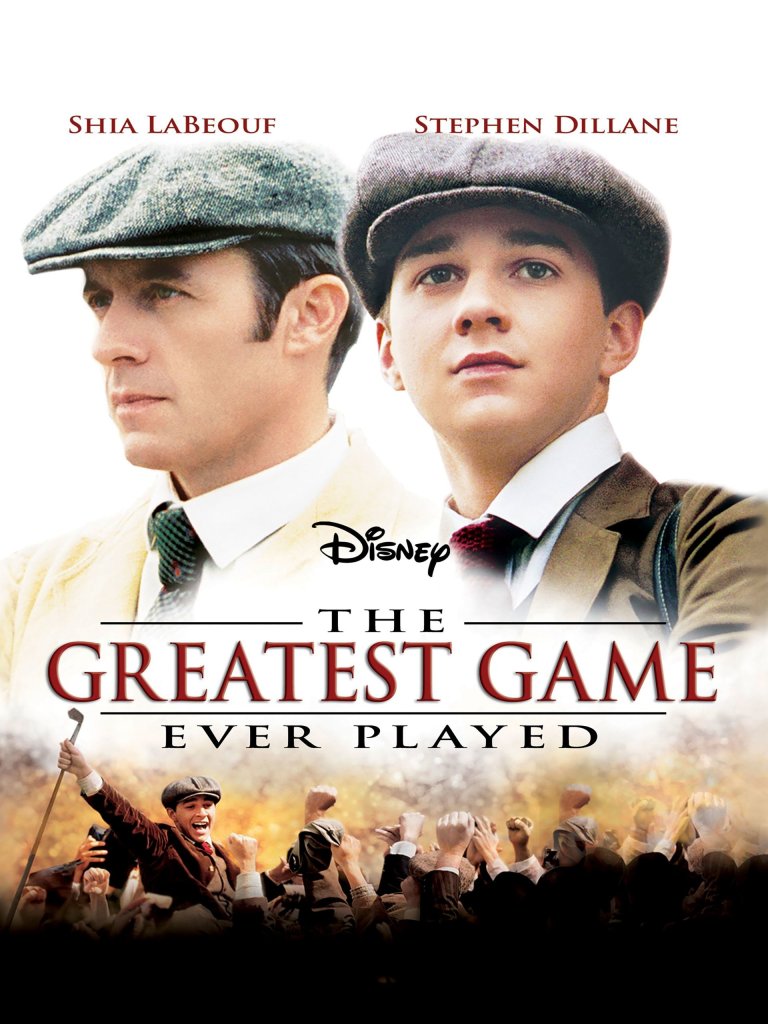

Their paths would cross again 13 years later on the Brookline golf course. Shia LaBeouf portrays Francis as a 20-year-old, his passion for golf having now blossomed into a mastery of the game. Encouraged by a solicitous club member, he competes in Massachusetts’ amateur competition.

Francis eventually accepts an offer to compete in the U.S. Open when it’s held in Brookline, chiefly so he can play on the same course as Harry Vardon and another British golf great, Ted Ray (Stephen Marcus). Circumstances leading up to that prestigious tournament spur another odd turn of events. After Francis’ caddie unexpectedly quits on him before the first day, he selects a replacement caddie: spunky 10-year-old Eddie Lowery (Josh Flitter), whose wit and spirit would prove instrumental to Francis’ game.

Inspirational sports pictures invariably follow certain tropes. The inevitable Big Game pits our fire-in-the-belly underdog against the arrogant champ. The Greatest Game Ever Played has its share of clichés, particularly Francis’ disapproving father and a love interest who wafts in and out of relevance, but the movie subverts other traditions of the genre. There is no villain in the piece, at least not when it comes to the golf tournaments. Both Francis Ouimet and Harry Vardon share a common enemy, that being the class system of their time. These products of working-class upbringing must prove their mettle in a sport that had long been the domain of wealthy white gentlemen.

Despite Vardon’s worldwide fame, he remains forever an outsider among the British aristocracy that treats him like hired help. The situation is no better on this side of the pond. When Francis enters the amateur competition, he is scoffed at by the Brookline club members who refuse to acknowledge him as anything but a lowly caddie.

Golf isn’t the most exciting spectator sport, but actor-turned-director Bill Paxton scores points for finding visually compelling ways to dramatize the tournaments. Through use of a camera-mounting Technocrane, viewers have the vantage point of the golf ball sailing through the air, slicing through trees before rolling gently toward the green. Paxton and cinematographer Shane Hurlbut use an array of tricks – obtuse camera angles, quick editing, slow-motion – but the cinematic pyrotechnics never obscure our ability to follow the action.