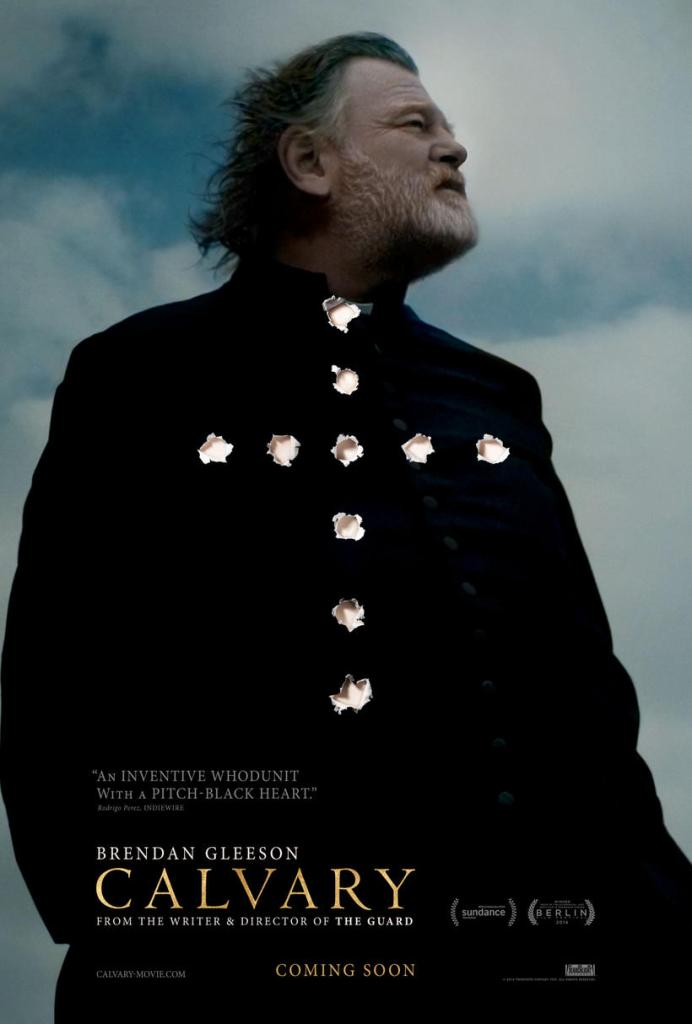

Brendan Gleeson exudes world-weariness as if it were a pheromone. Craggy and thick-bodied, his eyes hinting at untold sadness, he routinely makes a strong presence in most of his movies, no matter how modest the part. And he is at his dour best in Calvary, a tough, theologically minded film in which Gleeson portrays a Catholic priest in a small Irish coastal village.

Calvary writer-director John Michael McDonagh, who had worked with Gleeson in 2011’s The Guard, knows how to maximize the actor’s quietly ferocious authority. That know-how must run in the family; McDonagh’s playwright-filmmaker brother, Martin, has used Gleeson to tremendous effect for In Bruges and The Banshees of Inisherin. Calvary boasts a strong cast and a smart screenplay, but its emotional heft hinges on Gleeson’s charisma as beleaguered Father James.

He is mostly successful.

Calvary grabs your attention immediately. In confessional, an unidentified man reveals he was 7 years old when a priest raped him. “That’s certainly a startling opening line,” Father James says. The confession grows even darker. The sexual abuse continued for years, says the voice on the other side of the screen in the confessional booth. And for the sins of that predatory priest, now deceased, the confessor vows to kill Father James – an innocent, a “good” priest – in a week’s time. Enough time, says the confessor, for the father to get his “house in order.”

That’s a tall order in a parish as troubled as this one. Father James knows who his would-be assassin is but keeps that identity from church authorities and law enforcement – as well as the movie audience – as he goes about trying to counsel his parishioners. The “Who’ll do it?” mystery is a clever device that adds weight to the priest’s encounters.

The surrounding seascapes are idyllic; its inhabitants are anything but. The townsfolk include a self-destructive tramp (Orla O’Rourke), her menacing lover (Isaach De Bankole) and bitter husband (Chris O’Dowd), an atheistic doctor (Aidan Gillen), a male prostitute (Owen Sharpe), a sexually frustrated misfit (Killian Scott), a callow richie (Dylan Moran) and an imprisoned serial killer (Domhnall Gleeson, the star’s son). Father James slogs on with them all, as well as a visit from a sometimes-suicidal daughter (Kelly Reilly) from his pre-priesthood life, but his advice isn’t particularly welcome.

Most of the parishioners are cynical, angry and dismissive of the church. They deride the priest as he goes about his duty in the shadow of his own mortality. This can make for an interesting dynamic in Calvary. McDonagh’s writing is sharp, often wickedly funny and undeniably meaty. But there is no mistaking the larger parable on display.

And the obviousness of that strain for big meaning – a village of sin-addled archetypes, various meditations on death, a contrived ending – chafes a bit. “That’s one of those lines that sound witty but don’t really make much sense,” Father James says upon hearing one particularly pithy remark. It is a critique that too often applies to Calvary itself, in spite of Gleeson’s brilliant attempt to temper McDonagh’s loftier ambitions.