Serpico is gritty. It’s rough around the edges. It’s mired in an on-the-mean-streets-of-New York-in the-1970s vibe. In short, it’s a Sidney Lumet movie.

Al Pacino delivers an indelible, iconic performances as Frank Serpico, the real-life undercover cop who blew the whistle on widespread New York City police corruption in the early ‘70s. The movie begins with a jolt. We see a bloodied Serpico, having been shot in the face, rushed to a hospital. In flashbacks that span several years, we learn there are plenty of NYC police officers who gleefully would have put a bullet in the titular character.

It’s not much of a spoiler to say that Serpico survives the shooting (as of this writing, the flesh-and-blood Frank Serpico will turn 87 this year) and eventually testified before a grand jury about his crooked colleagues.

No one could do hard-bitten, naturalistic drama like director Lumet. He was at his creative apex during this period, and would go on to make Dog Day Afternoon and Network only a few years later. Lumet’s visual style here is deceptively unshowy, always in service to the story, although he isn’t well-served by Mikis Theodorakis’ bloated score. Shot in 110 locations, the movie also exudes New York at a specific time. You can almost smell the place.

Based on a nonfiction bestseller by Peter Maas and scripted by Waldo Salt and Norman Wexler, the biopic covers a lot of ground, albeit with mixed results. Two of Serpico’s girlfriends (played by Cornelia Sharpe and Barbara Eda-Young) flit in and out of the narrative, mainly to illustrate how the stresses of his job impact his personal life.

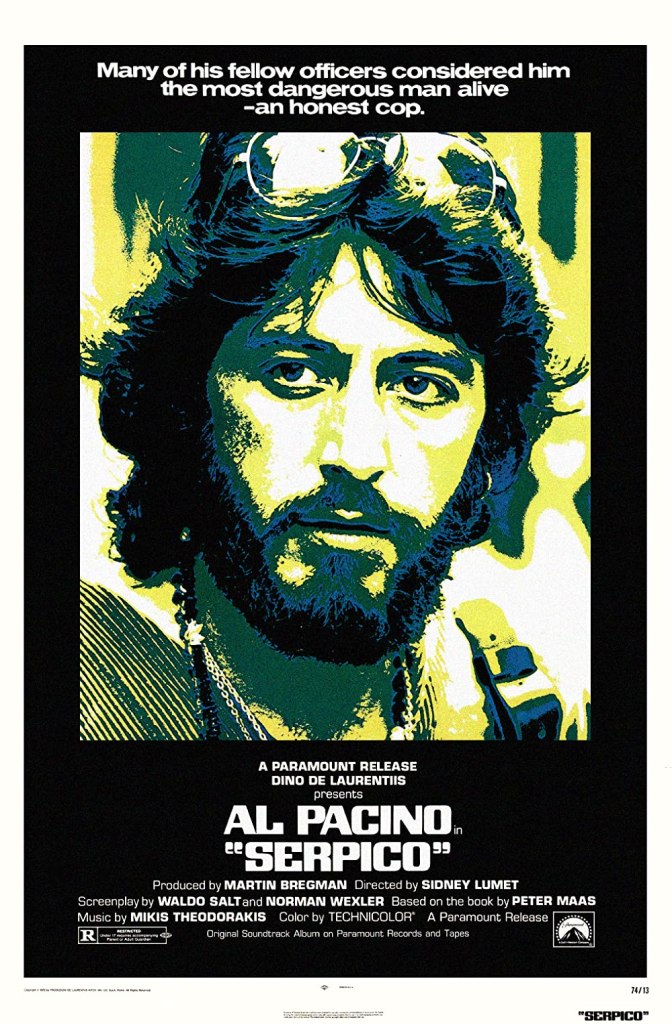

It quickly becomes clear that our hero wasn’t especially popular with his peers even before he testified. With long, shaggy hair and a hippie wardrobe – Pacino’s Serpico occasionally resembles a streetwise Tony Orlando – he is derided by other cops for his appreciation of ballet and books.

That tension escalates as Serpico recognizes the slow drip of compromise and corruption that permeates the police force. One of the movie’s more effective strategies is the slow but steady buildup of transgressions. Early on, the infractions are minor; the owner of a diner gives Serpico and his patrol partner free lunches in exchange for help with parking tickets. Once promoted, Serpico finds himself in a precinct where his colleagues skim gambling money. Serpico’s refusal to take part wins him no friends. “It’s incredible,” he confides to a friend, “but I feel like a criminal because I don’t take money.”

Eventually Serpico is assigned to a different precinct that he’s assured is “as clean as a hound’s tooth.” The description proves inaccurate, as he simply finds a more streamlined operation of bagmen and bribes. Serpico gets no help from police leadership more interested in avoiding bad publicity than cleaning house.

Pacino’s first big role after The Godfather secured his superstardom as well as a second Oscar nomination. And for good reason. He is sensational as the mercurial cop struggling to do the right thing in an environment where right and wrong seem malleable at best.

While Pacino carries the film on his capable shoulders, Lumet populates the edges with strong character actors such as John Randolph, Jack Kehoe and Tony Roberts. In uncredited bit parts are several actors who would go on to successful careers, including Judd Hirsch, Kenneth McMillan, F. Murray Abraham, Tony Lo Bianco, M. Emmett Walsh and Tracey Walter.

One response to “Serpico (1973)”

[…] place it squarely in line with the director’s string of 1970s-era masterworks that included Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon and […]

LikeLike