“You are not the kind of guy who would be at a place like this at this time of the morning.” –Jay McInerney, Bright Lights, Big City.

Alfred Hitchcock said he preferred making movies adapted from marginal novels instead of top-shelf literature. The latter, he reasoned, already had been defined in an artistic medium that didn’t necessarily translate easily to a visual sensibility. It’s a thought worth remembering with Jay McInerney‘s 1984 debut novel Bright Lights, Big City. While it certainly falls short of classic lit, the author’s sharp prose and quirky second-person narration don’t come through in James Bridges’ film adaptation.

Bright Lights the novel sparkled not because of its fairly pedestrian storyline, but because of McInerney’s telling. Among the Brat Pack literati of the 1980s, Bright Lights, Big City was the snooty, sophisticated older brother to Bret Easton Ellis‘ Less Than Zero. Both novels examined ennui, soullessness and cocaine in the Reagan era, but McInerney approached his subjects with a warmth and humor that eluded Ellis and other young scribes of that era.

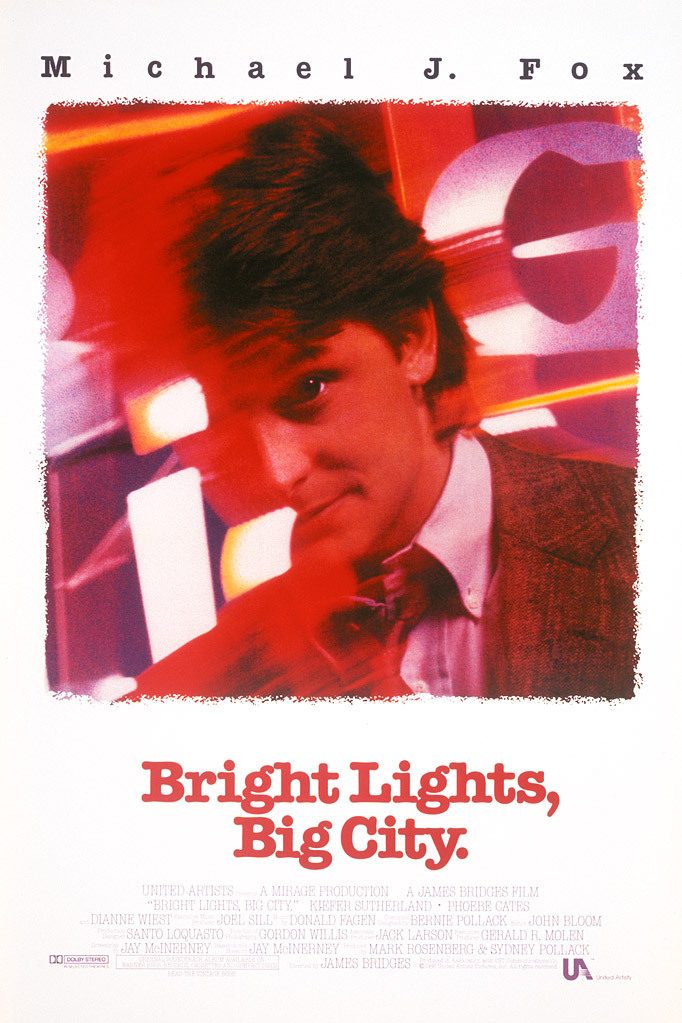

Stripped of the novel’s vigorous writing, the movie version of Bright Lights, Big City is a lackluster affair. Michael J. Fox plays against type as Jamie Conway, a Midwestern writer living in the Big Apple and slaving away in the fact-check department of a New Yorker-type magazine. He is in the depths of depression. Jamie has been dumped by his fashion-model wife Amanda (Phoebe Cates) and he is still nursing the psychological wounds of losing his salt-of-the-earth mother (Dianne Wiest) to cancer a year earlier. As a remedy to such grieving, Jamie (basically a semi-fictional stand-in for McInerney) hangs out at trendy clubs with pal Tad Allagash (Kiefer Sutherland) and snorts prodigious amounts of what Jamie memorably dubs “Bolivian marching powder.”

That’s about it. Things happen in Bright Lights, but the plot proceeds with not even a whiff of surprise, and almost as little emotion. The characters are too vapid to elicit much interest – even with Jamie, an unusually passive protagonist. Wiest has some poignant moments in flashback, but even this narrative thread feels like she is serving as a sort of placeholder for something else that never arrives. Tellingly, Jamie tells a coworker (the underused Swoosie Kurtz) why his wife left. “She wanted to live a magazine ad, and I wanted to live a literary cliché.” Well, at least Jamie is living his dream.

Part of the problem is Fox, a good actor who was woefully miscast. Other actors who had sought the role included Alec Baldwin, Tom Hanks and Judd Nelson. Any of them likely would have made a better fit than Fox, whose boy-next-door vibe is at odds with Jamie’s self-torment.

The movie boasts flashes of the book’s wit, particularly Jamie’s dissertation on the appeal of the New York Post and his fascination with an ongoing Post story involving a “coma baby,” but such episodes are saddled between sluggish, overly talky stretches. It is an unfortunate final work for director Bridges (The Paper Chase, The China Syndrome) who died of cancer several years after Bright Lights, Big City.