Critics of our criminal justice system don’t have to search for nightmare scenarios of wrongful convictions. From coerced confessions to exonerations through DNA testing, the past several decades are rife with tales of injustice that would have given Kafka the willies. It says something about the horrific saga of the West Memphis Three that their experience still manages to be so shocking.

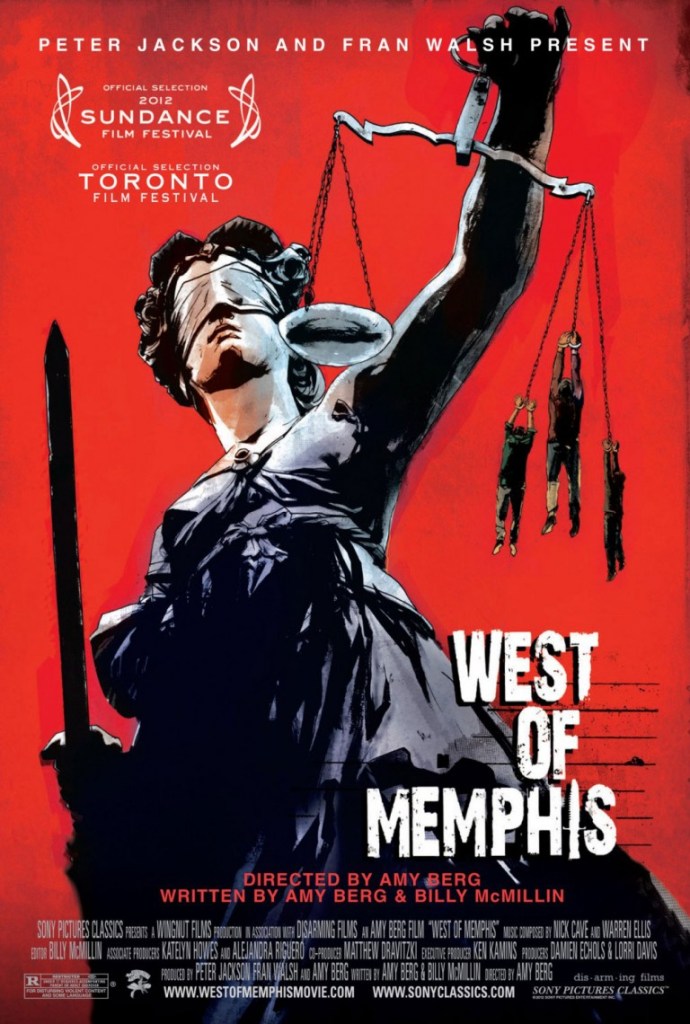

One might have thought that three HBO documentaries, the Paradise Lost films of Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky, would have been sufficient to tell this story. But West of Memphis is an essential chronicle of how the judicial system can go horribly wrong with the misinterpretation, whether deliberate or inadvertent, of just a few facts.

In May 1993, the bodies of three 8-year-old boys — Stevie Branch, Christopher Byers and Michael Moore — were found in a creek along Robin Hood Hills in West

Memphis, Ark. They were naked, hogtied with shoelaces, and covered in slash marks. Investigators, determining the murders had all the trappings of a satanic ritual, wound up charging three troubled youths who seemed likely to be caught up in occultism: Damien Echols, 18; Jessie Misskelley, 17; and Jason Baldwin, 16. Misskelley, who had an IQ of 72, offered up a confession in the wake of a grueling, 12-hour interrogation.

West of Memphis uses archival and contemporary footage to illustrate how the killings’ more sensationalistic aspects colored the trial. Jurors saw graphic photos of the victims and heard expert testimony about satanism. They heard from a jailhouse informant how the defendants had mutilated the genitals of one of the boys.

Echols received a death sentence, while Misskelley and Baldwin were sentenced to life terms.

Serious doubts about the prosecution’s case surfaced shortly after the verdict. Misskelley’s heavily edited confession had stemmed from leading questions. Key prosecution witnesses recanted their testimony. A crush of forensic experts scoffed at the notion of satanic ritual, contending instead that snapping turtles and other animals in the creek bed had inflicted the injuries.

The discrediting of the occult angle changed the sense of the crime itself, suggesting that the perpetrator might have known the victims beforehand.

Oscar-nominated filmmaker Amy Berg (who made another powerful documentary about perverse injustice, 2006’s Deliver Us from Evil, painstakingly builds a case for the innocence of the West Memphis Three. But that is only half her agenda. West of Memphis also posits that the actual killer could be the stepfather of one of the boys.

The case against that man, Terry Hobbs, gets considerable heft from the doc’s producers, Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh, who made The Lord of the Rings trilogy and evidently sank some money into investigating Hobbs. Some of what they discover is compelling, particularly DNA analysis of hair found at the crime scene. Other scraps of information — such as third-hand suggestions pointing to Hobbs’ culpability — are hardly worth the trouble.

Clocking in at nearly two and a half hours, West of Memphis veers a bit — only a bit — from exhaustive to exhaustion, something that could have been remedied with a little less from high-profile supporters Eddie Vedder and Henry Rollins. But the star wattage, a reminder that fighting for the freedom of the trio was as much a celebrity cause as it was cause célèbre, has its instructional use, too.

Few convicts who claim their innocence get the attention of a Jackson or a Johnny Depp. It’s worth noting the admonition of Echols in a prison interview: “This case is nothing out of the ordinary. This happens all the time.”