Man-versus-nature tales don’t get much more harrowing than the real-life one involving Aron Ralston. You aren’t likely to recognize the name, but you might know the incident that made him famous.

In May 2003, Ralston was mountain climbing in a remote section of Utah when a boulder crushed his right hand and wrist. Trapped for five days with little food and water, the 27-year-old eventually freed himself by using a pocketknife to cut off his own arm.

It’s a jaw-dropper story, but not necessarily surefire material for the multiplex. Much could have gone wrong in the cinematic adaptation of Ralston’s 2004 memoir, Between a Rock and a Hard Place. It could have been too excruciating or too sanitized, too sensationalized or too tedious.

So it’s something of a miracle that 127 Hours is great filmmaking. Director Danny Boyle is a dazzler with visuals, and he makes full use of his bag of tricks here, employing everything from split screens and hyperkinetic edits to oblique angles and camera movements that spit in gravity’s eye. Such flamboyance is not just a case of directorial indulgence (which, by the way, cannot be said of all Boyle’s movies). Rather, it reflects the rapturous spirit of Ralston, who, as played by James Franco, is an amiable adrenaline junkie.

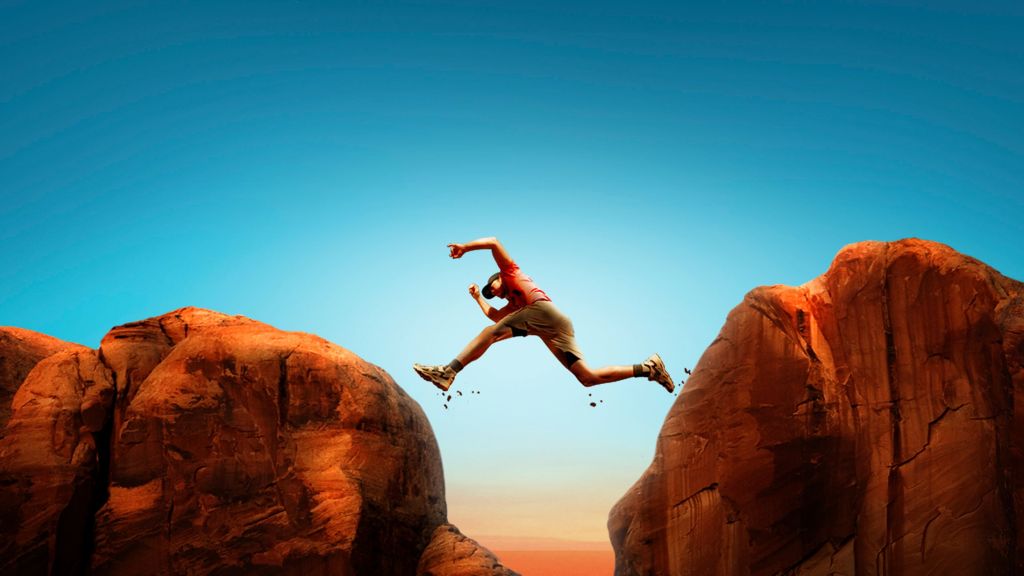

Franco’s Aron is an appealing hero, particularly fortunate since Franco appears in nearly every frame here. Exuding a roguish charm and humor that either stem from supreme confidence or just plain solipsism, he is fascinating. Early on, Aron meets two female hikers (Kate Mara and Amber Tamblyn) who are lost. He helpfully leads the pair through a shortcut that is equal parts terrifying and spectacular. “You’re batshit!” observes one of the hikers in a tone that makes it evident she means no insult.

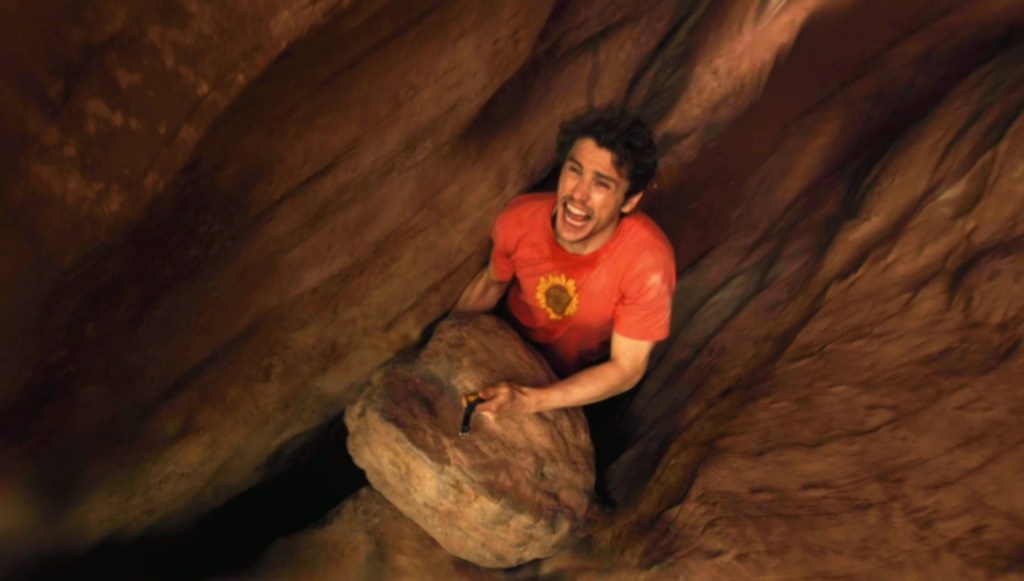

At the film’s core is Aron pitted against the rock that smashes his hand and traps him in a forgotten crevice of Bluejohn Canyon. Armed (ahem) with only a few tools and a camcorder, he spirals through an existential journey in which his waking horror is interspersed with memories and febrile imaginings. These stream-of-consciousness scenes are a wonder of stutters and bursts, capturing the insanity of his predicament and the genuine reassessment of a lifetime spent keeping people at (forgive me) arm’s length.

The climactic amputation is as disturbing as you might expect, and Boyle ups the ante with a deliriously inventive sound mix that makes audiences aware of every severed nerve (think a nightmare version of the old board game Operation). Still, the scene is vital viewing and, perhaps ironically, triumphant.