Critics swooned when Michael Clayton hit theaters in the fall of 2007, and rightly so. Here was the sort of legal thriller, went the conventional wisdom, that John Grisham movies always promise to be but rarely are: Smart, complex, suspenseful. The collective fawning was more than justified. Michael Clayton is just about pitch perfect, an elegantly crafted nail-biter that makes most other films of its ilk look dunderheaded by comparison.

The title character, portrayed by George Clooney, is one of the most valuable members of high-powered New York law firm Kenner, Bach & Leeden. But he’s not an attorney — not a practicing one, anyway. Michael is the firm’s allotted fix-it man, a self-described janitor skilled at mopping up the dirty little secrets of wealthy clients and lawyers. From this scenario, writer-director Tony Gilroy fashions a classic hero’s journey (Joseph Campbell would be proud) that affords Michael a chance at redemption, even as he seemingly sinks deeper into an abyss of corruption.

Michael’s plight parallels that of Arthur Edens (Tom Wilkinson), a brilliant attorney for the firm who has spent six years of his professional life — “six years scheming and stalling and screaming,” as he puts it — in service to a single client, U/North, an ADM-type corporation immersed in a $3 billion class-action lawsuit over deadly pollutants. Trouble arises when Arthur, who is bipolar, stops taking his meds. In the midst of a deposition in Milwaukee, he strips naked and chases after one of the plaintiffs. Michael is dispatched by the firm’s top dog (Sydney Pollack) to corral Arthur and get him back on track.

Michael is friends with Arthur, but the mission proves difficult. The attorney insists his meltdown has nothing to do with manic depression and everything to do with an epiphany about long defending a company that he knows is guilty.

As the title indicates, however, this is chiefly Michael’s story. The guy is in dire straits, owing more than $75,000 to some scary people in the wake of a failed restaurant. Muzzling Arthur might be his only way out of debt, especially with Kenner Bach about to enter into a merger that puts his future employment in question. But then the stakes get higher when U/North’s workaholic in-house counsel, Karen Crowder (Tilda Swinton), resolves to take matters into her own hands.

If that sounds like I just gave away the entire storyline, fear not. It’s just the launching point. Michael Clayton is one of those happy works of mainstream Hollywood in which the disparate elements of filmmaking coalesce magically. Gilroy, a top-tier screenwriter whose credits include the Jason Bourne franchise, has an astonishingly self-assured directorial debut here. He helps himself with a magnificent script rife with ingenious plotting, sharp dialogue and a knack for ratcheting up the tension without sacrificing the nuances.

But Gilroy is inspired throughout. Exposition is presented with flourish, and never at the expense of keeping the story moving. Characterization is drawn in deft, clear strokes; a smartly edited scene in which Swinton agonizingly rehearses for a puff-piece media interview imparts everything you need to know about Karen’s insecurities, misplaced priorities and blackened humanity. Gilroy’s narrative choices are also ambitious. Michael Clayton’s nonlinear first act heightens suspense even as it confuses half-alert audiences.

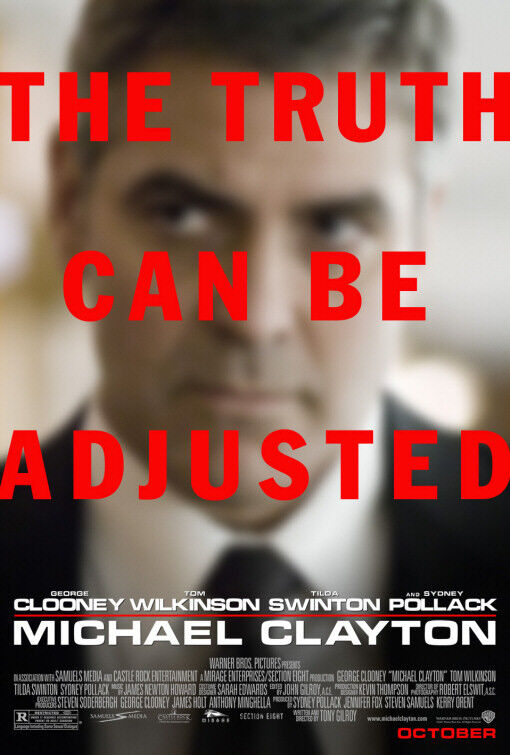

For his initial outing, Gilroy has assembled a first-rate cast. Clooney is at the peak of his movie star powers. While not exactly dialing down his commanding screen presence, Clooney makes Michael Clayton a bit scruffy, a seen-better-days fixer teetering on the edge.

But the supporting players are equally outstanding. As the bipolar attorney whose moral dilemma sparks Michael’s conscience, the late, great Wilkinson lends a soulfulness to what could easily have been a scenery-chewing performance. And Swinton, whose performance earned an Academy Award, is his equal as a reluctant villainess.

The sleek look of the film is taken care of by ace cinematographer Robert Elswit, who channels the gods of ‘70s cinema (namely Gordon Willis and Owen Roizman) in exquisite blacks and browns. Michael Clayton does not pretend to offer lofty truths or big social messages. All it wants to do is keep you on the edge of your seat. On that count, it is about flawless.