Stanley Kubrick, arguably the greatest filmmaker of his generation, shuffled off this mortal coil 25 years ago today. He was 70 years old. Only six days earlier, he had given Warner Brothers the final cut of what would be his last motion picture, Eyes Wide Shut.

Kubrick didn’t make me a cinephile, but he did make me want to make movies. He’s why I spent my teen years devouring every great film I could find (and in an era before streaming, no less). He’s why I went to USC film school. And in a more dubious tribute, his was the name I used for a fake ID I had bought at Oklahoma City’s Old Paris Flea Market the summer before going to college.

That freshman year, I was at a block party in UC Santa Barbara when two police officers stopped me for being drunk and making a general ass out of myself. They asked for identification, and without hesitation I stupidly handed over that ID. That night I quickly learned Californians are more film-literate than the 7-11 cashiers back in Oklahoma. “Well, well, well!” the officer snorted derisively. “Lookie who we have here! Mr. 2001 himself!”

Kubricks’s commitment to his craft was astounding. He obsessed over every shot, cultivating a reputation for numerous takes with his actors — sometimes numbering in the hundreds. The repetition reportedly contributed to Shelley Duvall’s nervous breakdown on the set of The Shining. It prompted Harvey Keitel to quit Eyes Wide Shut.

But Kubrick knew what the wanted. “When you think of the greatest moments of film,” he once observed, “I think you’re almost always involved with images rather than scenes, and certainly never dialogue.” While that’s a somewhat absurd dismissal of dialogue, there is little disputing that his canon is rife with indelible visuals. Think Dr. Strangelove’s Slim Pickens riding the atom bomb like he’s in a rodeo, or Jack Nicholson’s psychotic grin after killing Scatman Crothers in The Shining, or the Star Child of 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Here is my ranking of every Kubrick movie. Just as he divided audiences, I am sure this ranking will rankle some. Stanley would have wanted it that way.

13. Fear and Desire (1952)

A baby director just learning the craft. There’s little in this amateurish war picture that portends the genius who would emerge only four years later in The Killing.

12. Killer’s Kiss (1955)

Killer’s Kiss is hardly successful, but fans of the director can spot flashes of inspiration in this tale of a down-on-his-luck middleweight. The climactic fight in a warehouse of mannequins is pretty nifty, and Kubrick’s experience as a photographer for Look magazine is evident in the gritty New York City locales. While Kubrick would only make one more full-fledged noir with The Killing the following year, the worldview of the genre reverberated throughout his career. “The characteristics of the noir genre in particular must both have confirmed and heightened his fatalism, his sense of despair and his innate pessimism,” Michael Ciment wrote in his book, Kubrick. “The fear of failure, the paranoid vision of a hostile world, though they would be explored more fully in his subsequent work, were already cohesively articulated in these early films.”

11. Spartacus (1960)

After Kubrick’s successful collaboration with Kirk Douglas in 1957’s Paths of Glory, the star tapped the young filmmaker to direct this epic of a Roman gladiator-turned-freer of slaves. Spartacus is a banger of a spectacle with an all-star cast — including Laurence Olivier, Tony Curtis, Jean Simmons, Charles Laughton and Peter Ustinov — but it was a miserable ordeal for the director. Douglas treated him as a hired hand whom he could fire over any disagreement. Kubrick left the experience determined never to accept less than complete control when making a movie. It was a promise he kept.

10. Eyes Wide Shut (1999)

Kubrick’s final feature was a commercial success during its theatrical release but took a critical drubbing. The passage of time, however, has led to a reassessment of Eyes Wide Shut. These days, many consider it a masterpiece. One thing is for sure; Warner Brothers’ marketing, which characterized Eyes Wide Shut as boundary-pushing eroticism, did it no favors. There was no onscreen sex, and a climactic masked orgy has all the steamy energy as a Rotary luncheon. At the time, The Washington Post’s Stephen Hunter joked that Eyes Wide Shut “turned out to be the dirtiest movie of 1958.” Come without libidinous expectations, however, and the movie’s dreamlike artifice and general weirdness are a kick. Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman, then Hollywood’s biggest power couple, play Manhattan elites Dr. Bill and Alice Harford, whose marriage is curiously thrown into turmoil after Alice confesses to a sexual fantasy involving another man. A shaken Bill wanders a faux NYC hoping to experience his own sex fantasy, but to no avail. That a doctor who looks like Tom Cruise can’t get laid in New York underscores a sly humor that movie audiences missed at the time. It’s not for nothing that Kubrick had first approached Steve Martin for the role.

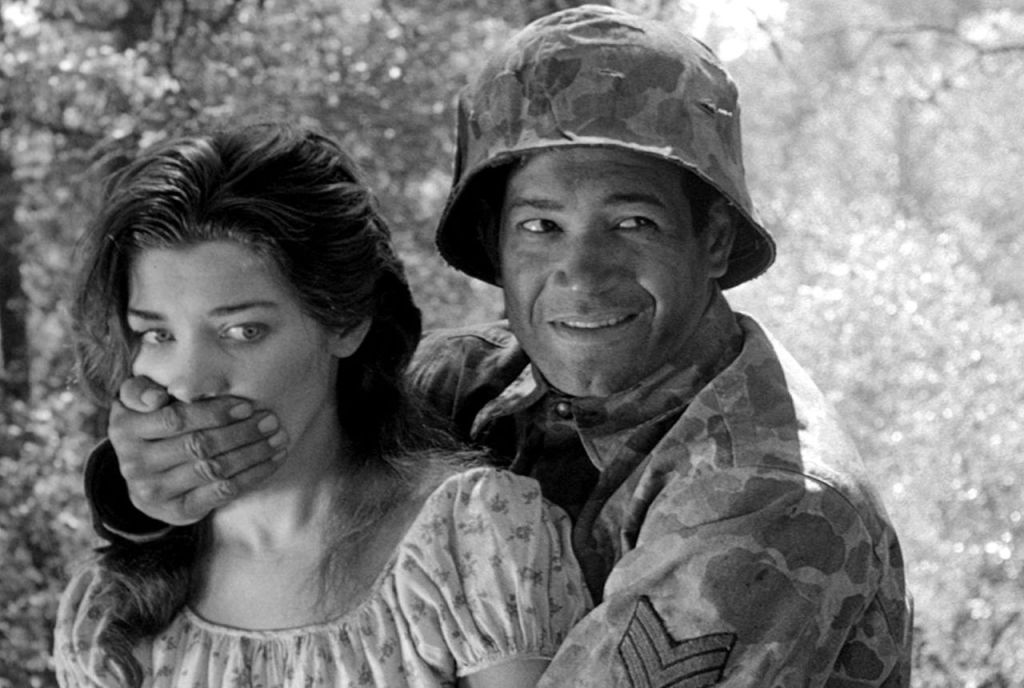

9. Lolita (1962)

If Kubrick took a movie-friendly book with Stephen King’s The Shining and turned it into something enigmatic, it’s an interesting coincidence that he took am ostensibly unfilmable novel, Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, and transformed it into mildly raunchy satire. Hollywood’s Production Code would be dead and buried before the 1960s were over, but its stodgy heart was still beating when Kubrick optioned Nabokov’s story of a pedophile’s obsession with an adolescent girl. The director and Nabokov, who wrote the script, sanded down the pedophilia angle. Sue Lyon was 16 when Kubrick tapped her to play the titular character, but she could have passed for 18. Aside from being coquettish, she doesn’t have much to do. The rest of the cast, however, is extraordinary. As the predatory Humbert Humbert, James Mason lends a pinched, calculated wickedness. Shelley Winters is both a punch line and a tragic figure as Lolita’s lonely mother, and Peter Sellers is let loose to do his multiple-character thing as Humbert’s rival for Lolita’s affection.

8. Full Metal Jacket (1987)

Kubrick’s Vietnam War opus suffers by comparison. Apocalypse Now had been released in 1979. Platoon was released the year before Full Metal Jacket. Hamburger Hill came out a month after Full Metal Jacket. The movie is essentially two stories. The first half takes place at Marine Corps training on Parris Island, S.C., where a vicious drill sergeant (R. Lee Army) terrorizes dense recruit Leonard Lawrence, whom he calls “Private Pyle,” after TV’s Gomer Pyle. As the young Marine bullied into madness, Vincent D’Onofrio proves himself to be a consummate actor. While the movie’s second half is more conventional war-pic terrain, the director’s eye for arresting visuals and technical mastery remains evident throughout.

7. The Killing (1956)

The Killing is where everything first clicked for Kubrick. Scripted by him and the great Oklahoma-born pulp novelist Jim Thompson, The Killing is a crackerjack noir bursting with style, from its Dragnet-ish voiceover narrator to its inventive, nonlinear narrative. The cast brims with terrific character actors, particularly Sterling Hayden, Elisha Cook Jr., Timothy Carey, and Marie Windsor putting the fatale in femme fatale. The picture’s nearly-nonexistent marketing sealed its fate as a commercial failure, but the studios took notice of the rapturous reviews from critics. The Killing is one of the best heist movies ever made.

6. The Shining (1980)

Stephen King made no secret of his disdain for Kubrick’s loose adaptation of the author’s rightly celebrated 1977 novel. That’s King’s prerogative, but the film version is one of the all-time great horror pictures. Film writer David Thomson credits The Shining as the director’s sole (!) masterpiece, “serenely unanchored in any fixed genre, effortlessly invented, inspired alike by the hollow brain of a house and the naughty little germ of a man, Jack.” As Jack Torrance, the recovering alcoholic and reluctant family man tasked with being caretaker for a sprawling hotel during a snow-bound winter, Jack Nicholson is all arched eyebrows, maniacal laughter and enough scenery-chewing to catch splinters in his teeth. In short, he is magnificent. But the images are what lodge in your brain: Those hypnotic Steadicam shots of Danny (kid actor Danny Lloyd) riding his Big Wheel through endless hotel corridors, blood pouring from elevator doors, a single typed sentence repeated on hundreds of pages of a manuscript, and, of course, the creepiest twin girls you would never want to come across. The Shining‘s haunting final shot might be the ultimate representation of the fatalism that permeated Kubrick’s movies.

5. Paths of Glory (1957)

Adapted from a 1935 novel based on a reall-life incident in World War I, Paths of Glory is still one of the most brutal, unflinching indictments of war ever committed to film. Kirk Douglas stars as a French colonel whose soldiers are saddled with an impossible mission and then court-martialed when things inevitably go south. The uncharacteristically restrained Douglas is surrounded by a slew of fantastic actors, particularly George Macready and Adolphe Menjou as the embodiment of an evil, class-conscious establishment, something that would crop up a lot in Kubrick pictures. The first writer to take a crack at the screenplay was Jim Thompson, with whom Kubrick and producer James B. Harris had worked on The Killing, but his script was deemed — to everyone’s surprise — too gentle. The final product assuredly has no such timidity.

4. A Clockwork Orange (1971)

Even by the standards of Kubrick, whose movies routinely divided critics, A Clockwork Orange was especially polarizing. The adaptation of Anthony Burgess’ 1962 novel initially earned an X rating for its nightmarish vision of a slightly futuristic Britain overrun by hooligans engaged in “the old ultra-violence.” Malcolm McDowell is terrifying (and disturbingly engaging) as Alex, the leader of the “droogs”; his rape of a woman during a home invasion, all while he belts out “Singin’ in the Rain,” easily remains one of the most upsetting scenes ever in a mainstream picture. And yet A Clockwork Orange is also filled with cheeky humor, high-flying satire, philosophical musings and a splashy production design. Film historian David Thomson is no Kubrick fanboy, so his praise of McDowell’s performance is worth noting: “McDowell was so alive then, so passionate and gloomy, so nasty and saintly. He breaks through Kubrick’s restraint — he makes the film love him in a way that had never occurred in Kubrick before.”

3. Barry Lyndon (1975)

A lot of critics (and audiences, too) dismissed Barry Lyndon as a snooze upon its theatrical release, but — as typically happens with Kubrick films — the successive years have rightly crowned it as an audacious masterpiece. Adapted from William Makepeace Thackeray’s 1844 The Luck of Barry Lyndon, it is firstly a technical marvel. Kubrick’s commitment to authenticity ensured that the picture would be naturally lit; some scenes are illuminated solely by candlelight. Ken Adam’s production design is flawless. Employing a picaresque approach, Barry Lyndon is a wry, cutting statement about humanity at its most callow and self-serving. And when it comes to self-serving callowness, no star of the 1970s could top Ryan O’Neil as the titular antihero.

2. Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964)

Kubrick’s cyanide-dipped mash note to the Cold War has lost some of its punch over the decades, but not its brilliance. In exploring how to approach the grim source material of Peter George’s 1958 novel Red Alert, the filmmaker noted the nonchalance with which people were beginning to accept the prospect of nuclear annihilation. “Dr. Strangelove was undertaken with the conscious aim of sounding an alert that would startle people to response and even resistance to such a fate,” writes Alexander Walker in Stanley Kubrick Directs. “And laughter, not for the first time, was the device selected to penetrate the sound-proofing of the paralyzed will.”

Strangelove also boasts some of the greatest comic performances of the 1960s, with Sterling Hayden and George C. Scott as pathologically gung-ho military generals and Peter Sellers crushing it as three characters, including the title role.

There are a thousand reasons I love the flick but sandwiched between reason #112 (the fearsome-looking booger in Hayden’s nose visible in low-angle shots) and reason #114 (“He, he’ll see everything; he’ll see the big board!”) is its spot-on political satire. President Merken Muffley (Sellers) explaining to a drunken Russian premier how an Army general “went and did a silly thing” by ordering a nuclear attack, Gen. Buck Turgidson (Scott) making lemonade out of nuclear lemons in the War Room, the Russian ambassador (Peter Bull) referencing the unimpeachable New York Times … it is all crazy and crazily authentic. Alas, Kubrick did not live to see just how crazy global politics would get.

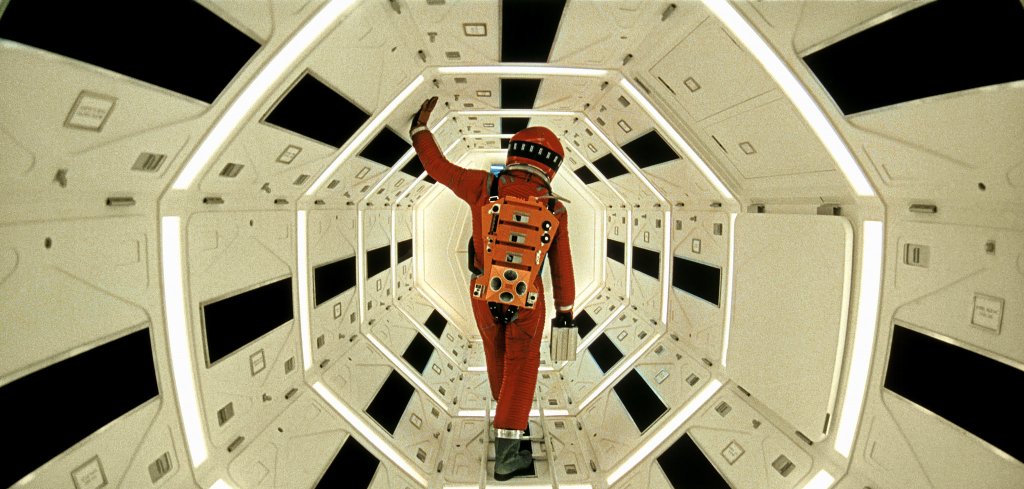

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

It’s not the most original #1 selection but, hey, it is what it is. How can it not be 2001? Secluded in his Shepperton Studios outside London, Kubrick spent nearly four years shooting the picture that would expand what film could be. Written by Kubrick and science-fiction author Arthur C. Clarke (and based on a Clarke short story), 2001 is a sort of cinematic Rorschach test. You can analyze it frame by frame and argue over its meaning, or you can just let its spectacle of sound and image wash over you. From the opening “The Dawn of Man” sequence to a phantasmagorical ending, its openness to interpretation is part of its allure. Still, some themes are pretty straightforward, namely humankind’s troubled relationship with technology. And much ink has been spilled musing over how the flesh-and-blood humans of 2001 are cardboard bores, while the most interesting being is the HAL-9000 artificial intelligence system — or HAL, for short — that operates the Discovery One spaceship headed toward Jupiter.

The movie is breathtaking. Doug Trumbull’s special effects might be modest by today’s standards, but Kubrick’s glorious presentation of them somehow feels reinvigorating no matter how many times one rewatches the film. The music is critical. Alex North composed an original music score, only to discover at an early screening that Kubrick had opted instead to keep the classical pieces he had used as placeholders. It was the right decision. Johann Strauss’ “The Blue Danube” is an interesting juxtaposition to both the majesty and innocuousness of space travel. And the use of Richard Strauss’ “Thus Spoke Zarathustra” every time we see one of those mysterious monoliths is powerful enough to have withstood more than 50 years of parody (most recently in the opening to Barbie).

The famously perfectionist director pushed his crew to their limits, as was his custom. Case in point: For “The Dawn of Man,” Kubrick was determined to film the ape-people mothers nursing their babies convincingly. His makeup artist, Stuart Freeborn, initially wanted to use wires to manipulate baby chimps so it looked like they were suckling the prosthetic breasts worn by actors. Kubrick nixed the idea as cheating. Freeborn eventually found a workaround, but was then stymied when Kubrick shot down his plan to keep the baby chimps latched by slathering honey on the fake teats. “No, that’s no good,” groused the director. “They’ll suck that off too quickly. I want to see them really suckling.”

Not everyone minded the demands from the genius filmmaker. Daniel Richter, who portrayed one of the ape people, appreciated Kubrick spending hours on a single shot. As he told writer Michael Benson in Space Odyssey: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke and the Making of a Masterpiece, Kubrick “was going to be learning and crafting and building something that a lesser director would have stopped along the way someplace, or settled for something less.”