From Pip to Holden Caulfield and everything in between (as well as before and after, for that matter), the coming-of-age story has been indispensable. There are a multitude of variations, of course: a first love or heartbreak, that first encounter with mortality, learning a momentous truth about a parent or friend, discovering right and wrong.

You get the idea. Regardless of the particulars, however, the best coming-of-age stories have universal appeal because growing up is something we all have to go through, even if we do so screaming and kicking.

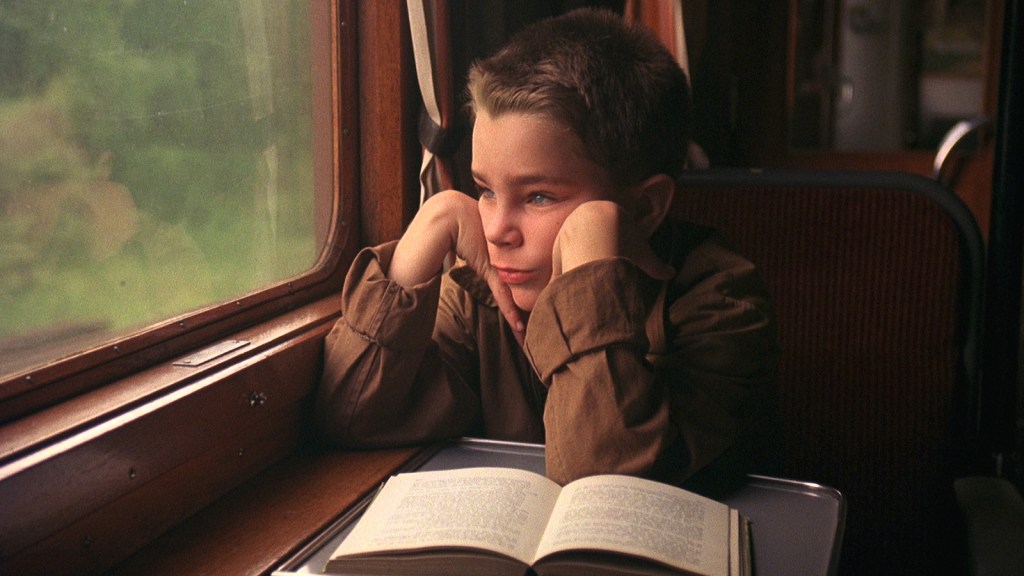

15. My Life As a Dog (1985, dir: Lasse Hallström)

Sometimes coming of age is more about acceptance than empowerment. In My Life as a Dog, Anton Glanzelius is remarkable as Ingemar, a 12-year-old Swedish boy in the late 1950s. His rambunctiousness, while typical for a kid his age, is too much for his terminally ill single mother, prompting Ingemar to be pawned off on relatives in a small village. Ingemar’s subsequent adventures are tempered by his gnawing belief that he has been a burden. Lasse Hallström’s sophomore film is gentle, reflective and quietly affecting.

14. Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret (2023, dir: Kelly Fremon Craig)

Hollywood surprisingly took more than 50 years to adapt Judy Blume’s seminal YA novel for the big screen, but the wait was worth it. If Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret is a little too neatly packaged for its own good (it bears definite traces of co-producer James L. Brooks), it is also witty, funny and warm. Abby Ryder Fortson is appealing as the title character (Margaret, that is) coping with a new school, a new group of friends, familial tensions and growing awareness of her bodily changes (that’s code for puberty). Rachel McAdams and Kathy Bates shine in supporting roles.

13. Real Women Have Curves (2002, dir: Patricia Cardoso)

America Ferrera was never better than in her film debut. In Real Women Have Curves, she is Ana Garcia, an 18-year-old Mexican American growing up in East Los Angeles, where she is caught between the financial needs of her family and a possible college scholarship to Columbia University. Ferrera delivers a heartfelt performance as a smart young woman who quietly but resolutely resists being defined by others, whether that be mass-media conventions of feminine beauty or the barbs from her self-loathing mother (Lupe Ontiveros). Patricia Cardoso directs with empathy toward all the characters in Josefina López and George Lavoo’s sensitively crafted screenplay. The movie signaled a pivotal moment for independent film, particularly in its unshowy testament to female empowerment.

12. Rebel without a Cause (1955, dir: Nicholas Ray)

Jim Stark is being torn apart. His mom is on his case, his dad doesn’t have his back, and the in-crowd at his new school are assholes. Jim’s problems mount tenfold when he is involved in a dangerous game of car chicken that ends with a classmate’s death. James Dean—who played Jim—died in a car crash only a month before Rebel without a Cause’s theatrical release, but his performance lives as a testament to his singular command of the screen. He might not be a terribly convincing teenager (Dean died at age 24), but his angst rings true. Co-stars Natalie Wood and Sal Mineo really were teens, and both give heart-wrenching performances. Alienated from dysfunctional homes, the trio create their own fantasy family—if only for an all-too-brief time. If director Nicholas Ray didn’t quite blow the lid off why kids from good homes turn to delinquency, the picture was still provocative enough for Tennessee Senator Estes Kefauver to accuse it of corrupting America’s youth—an admonishment he made before seeing it.

11. The 400 Blows (1959, dir: François Truffaut)

François Truffaut’s directorial debut was a milestone of the nouvelle vague, but The 400 Blows also happens to be a terrifically entertaining coming of age. Jean-Pierre Léaud, in his first of several Truffaut films, plays Antoine Doinel, a teenager trapped in an unhappy home life and an oppressive school system. Based partly on Truffaut’s own difficult childhood, The 400 Blows is unsentimental but affectionate toward its rebellious young protagonist. Antoine just cannot catch a break. Partial to bouncing around the streets of Paris, he comes across his mother in the arms of a man not his father. He steals a typewriter that leads to serious trouble. The film’s title might sound like something on PornHub, but it simply references a French expression—faire les 400 coups—which loosely translates to being a hellraiser.

10. Moonrise Kingdom (2012, dir: Wes Anderson)

Writer-director Wes Anderson and co-writer Roman Coppola know how to get to the crux of adolescent obsession: the exuberance, the earnestness and the flat-out weirdness. Our chaste lovers are Sam Shakusky (Jared Gilman) and Suzy Bishop (Kara Hayward), 12-year-olds who meet in the summer of 1965 on a mythical New England island. Sam, outfitted in crooked eyeglasses and coonskin cap, is an orphan who has trouble making friends. Suzy, burdened with quarrelsome parents, has trouble curbing a volatile temper. The two flee their respective adult supervision and rendezvous for adventure before summer’s end. She brings a suitcase filled with girls’ adventure books and a battery-operated record player. He takes camping gear and a corncob pipe. Together they dance on a secluded beach, read dime-store novels and celebrate an irresistible romance. Boasting several of Anderson’s regulars––including Edward Norton, Tilda Swinton and Bill Murray––Moonrise Kingdom reaches enchantment.

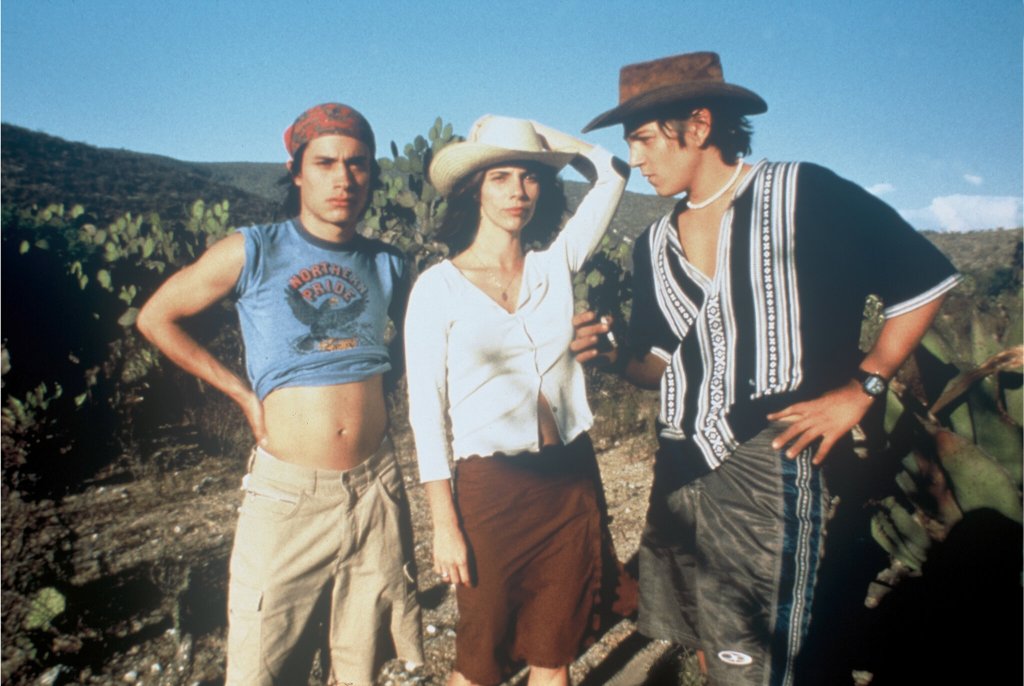

9. Y tu mamá también (1999, dir: Alfonso Cuarón)

Set in Mexico circa 1999, Y tu mamá también follows Tenoche (Diego Luna) and Julio (Gael García Bernal), two friends from upper-class families whose girlfriends are in Italy for the summer. Girl crazy and horny af, the boys have the ostensibly good fortune of embarking on an impromptu road trip with Luisa (Maribel Verdú), a Spanish wife who has run out on her philandering husband. Tenoche and Julio assume they will get laid, but Luisa’s presence proves to be the catalyst for unexpected turns. Against a backdrop of political unrest in Mexico, Cuarón––who wrote the screenplay with his brother Carlos––weaves a story about awakening to class, sexuality and the vicissitudes of life itself.

8. Kes (1969, dir: Ken Loach)

Billy Casper’s future looks bleak. He lives in the Yorkshire region of Northern England where it is assumed the boys will become coal miners like nearly all their fathers. The 15-year-old doesn’t have a father in his life, which appears to be a steady grind of reprimands at school and bullying from his older brother at home. Amid this hardscrabble routine, the stoic boy finds an escape with a kestrel that he dotes on and resolves to train. Adapted from the Barry Hines novel A Kestrel For a Knave, Kes is beautifully realized social realism from director Ken Loach. In searching for a suitable Billy, the filmmaker stumbled upon a local kid, David Bradley. Distinguished by his mournful eyes and angular face, Bradley’s revelatory performance captures the joys, the stings and––perhaps most important––the resilience of growing up.

7. Fish Tank (2009, dir: Andrea Arnold)

Fish Tank is imbued with gritty honesty, much like the angry girl at its center. Mia (Katie Jarvins) is a foul-mouthed, rage-filled 15-year-old stuck in a London housing project with her unhappy single mom (Kierston Wareing) and precocious younger sister (Rebecca Griffiths). When mom hooks up with a good-looking charmer (Michael Fassbender) who encourages Mia’s growing interest in dance, Mia finds herself inexorably drawn to him. Writer-director Andrea Arnold’s brand of social realism in her feature debut fits a British tradition that goes from Tony Richardson to Ken Loach (see #8 above), but Fish Tank has a fierceness and rawness all its own. Jarvis is extraordinary. She had no acting experience when Arnold’s casting assistant spotted the girl fighting with her boyfriend in a railway station.

6. Boyz n the Hood (1991, dir. John Singleton)

For his feature-length debut, writer-director John Singleton drew upon his own childhood experiences in South Central Los Angeles. The memories were still fresh for the filmmaker, only 23 at the time and newly graduated from the University of Southern California film school. Boyz n the Hood follows a tight-knit group of friends navigating life, but Singleton’s clear surrogate is Tre Styles (Cuba Gooding Jr.), a talented teenager sent by his single mom to live with his dad (Lawrence Fishburne) in Crenshaw. The story packs in a lot about friendship, fatherhood, race and poverty, but its themes are always in service to the movie’s vividly drawn characters. Gooding and Fishburne give standout performances, but Ice Cube and Morris Chestnut also do solid work. Boyz n the Hood made Singleton the youngest director ever nominated for a Best Director Oscar and the first African American to be up for the award. Tragically, Singleton’s canon is limited: he died in 2019 at age 51 after suffering a stroke.

5. Pather Panchali (1955, dir: Satyajit Ray)

Pather Panchali holds great historical prominence for world cinema, marking the debut of writer-director Satyajit Ray and being the first Indian film to break through with Western audiences. It also happens to be a tremendous story following a destitute Brahmin family living in rural Bengal in the 1910s. Our focal point is Apu (Subir Banerjee), the family’s mischievous young son, but Ray also takes great care in shaping Apu’s parents (Karuna Banerjee and Kanu Banerjee), older sister Durga (Uma Dasgupta) and Indir (Chunibala Devi), the withered auntie who benefits from Durga’s sticky fingers when it comes to the orchard next door. Influenced by Italian neorealism, Pather Panchali moves with a relaxed pace and tone that allows us to fix on small moments of beauty and grace. Apu raids his sister’s toy box to make a costume. He and Durga are ecstatic when they finally see a locomotive in person. They play in the downpour of a monsoon. Such images linger in my memory long after the final reel. Ray continued to chronicle Apu’s life with Aparajito the following year and The World of Apu in 1959.

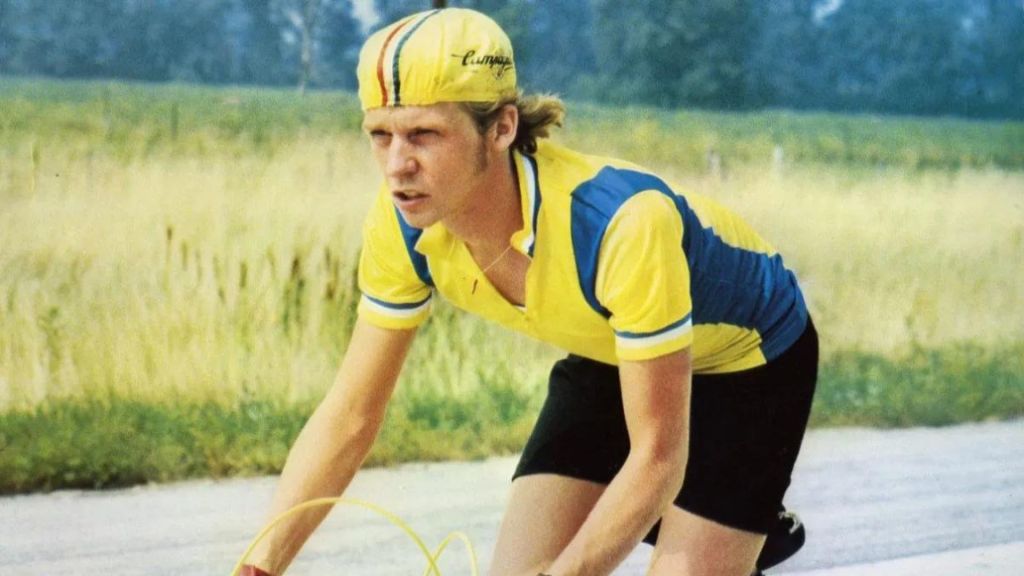

4. Breaking Away (1979, dir: Peter Yates)

This unassuming and utterly charming comedy-drama stars Dennis Christopher, Dennis Quaid, Daniel Stern and Jackie Earle Haley as teenage friends in Bloomington, Indiana. It is shortly after high school graduation, and the four spend their days hanging out, talking about girls and swimming in an abandoned quarry. None plan to attend college, much less Indiana University, which happens to be in their hometown. The sons of rock-cutting quarry workers, these products of working-class families expect lives not far removed from the paths of their parents––even though most of the quarry jobs have long since vanished. The lone exception might be Dave (Christopher), whose interest in cycling has morphed into an obsession with remaking himself as Italian. Paul Dooley and Barbara Barrie play his befuddled folks, and they steal most of their scenes. Dad is irritated enough that his son is shaving his legs as the “I-talian” cyclists presumably do, but things go too far when he renames the family cat “Fellini.” Breaking Away is all heart without yanking too hard on the heartstrings.

3. Boyhood (2014, dir: Richard Linklater)

This remarkable movie is a testament to the boldness and adventurousness of Richard Linklater. To chronicle a boy’s life, the writer-director and his Boyhood cast filmed in Texas for about a week every summer over a 12-year period. Other movies have captured the phenomenon of growing up, but Boyhood offers the exhilaration of watching that journey unfold in one fell swoop. We see the literal transformation of Mason Evans Jr. (Ellar Coltrane) from doughy 6-year-old to lanky college freshman. Sometimes the physical changes are jarring. If I hadn’t known better, I might have thought the actor playing Mason had been replaced between seventh and eighth grade. Within minutes, the boy is taller and slender, his voice having deepened; when it comes to special effects, Hollywood has nothing on puberty. While Ethan Hawke and Patricia Arquette are terrific as Mason’s parents (and Arquette won an Oscar for her performance), Linklater was especially fortunate when he gambled on casting Coltrane, who is excellent.

2. The Graduate (1967, dir: Mike Nichols)

Mike Nichols’ watershed comedy-drama underscores that a meaningful coming of age isn’t limited to teenagers and small children. Dustin Hoffman became an overnight sensation as Benjamin Braddock, fresh out of college but pissed at the world and adrift—literally and metaphorically—in the swimming pool of his parents’ comfortable Los Angeles home. Cue the alluring Mrs. Robinson (Anne Bancroft), the coolly contemptuous wife of his father’s business partner. “Mrs. Robinson, you’re trying to seduce me,” Benjamin intones in one of the picture’s more famous lines. “Aren’t you?” The Graduate quickly became a seminal document for a generation of disaffected youth determined not to become their parents. There are many reasons to adore it, from Buck Henry’s witty script to the lovely Simon & Garfunkel soundtrack to its wonderfully ambiguous ending. The leads are extraordinary. Nichols cast the then-unknown Hoffman because he fit the director’s vision of Benjamin as more nervous and insecure than the WASPy, athletic type described in the novella on which the film is based. Robert Redford, who had worked with Nichols in Barefoot in the Park on Broadway, lobbied hard for the role. He lost out after Nichols asked the ridiculously handsome actor how he handled being rejected by a woman. Redford didn’t understand the concept.

1. The Last Picture Show (1971, dir: Peter Bogdanovich)

The Last Picture Show was Peter Bogdanovich’s nostalgia-drenched homage to his director heroes like John Ford and Howard Hawks. Set in Texas circa the early 1950s and shot in gorgeous black and white by Robert Surtees, the film––Bogdanovich’s second after 1968’s low-budget Targets––far transcended mere imitation of the old masters. In using Larry McMurtry’s 1966 novel as source material, Bogdanovich embraced the freedom of New Hollywood to drill deep into the complexities of small-town life for a work that is sprawling, humane and elegiac. Our entry point is high school senior Sonny Crawford, played by sad-eyed Timothy Bottoms with an air of detached melancholy. While The Last Picture Show is primarily Sonny’s story, it also details the coming of age for several young residents of small-town Anarene, Texas, particularly Sonny’s friend Duane Jackson (Jeff Bridges) and Jacy Farrow (Cybill Shepherd). As the manipulative beauty who toys with the young men’s affections, model-turned-actress Shepherd made an indelible impression both on and off the screen; she and Bogdanovich began an affair during the shoot (while his then-wife Polly Platt served as production designer). As strong as the young actors were, they are overshadowed by Ellen Burstyn, Ben Johnson and Cloris Leachman; the latter two earned Oscars for their supporting roles.

Honorable mention: American Graffiti (1973, dir: George Lucas), Au revoir, les enfants (1987, dir: Louis Malle), Closely Watched Trains (1966, dir: Jirri Menzel), Cooley High (1975, dir: Michael Schultz), Germany, Year Zero (1948, dir: Roberto Rossellini), Lady Bird (2017, dir: Greta Gerwig), The Member of the Wedding (1952, dir: Fred Zinnemann), Stand by Me (1986, dir: Rob Reiner), To Kill a Mockingbird (1962, dir: Robert Mulligan)