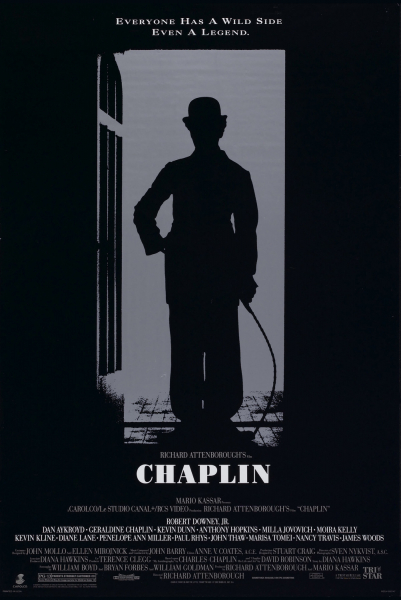

When Lord Richard Attenborough announced in the late 1980s his intention to make a biopic about Charlie Chaplin, the enterprise smacked of Oscar bait. Attenborough’s bloated prestige production, Gandhi, had nabbed the 1982 Academy Award for best picture, and Chaplin’s tumultuous life, peppered with scandals of sex and politics, was the stuff of epic storytelling. If Chaplin as subject matter wasn’t quite in the same league as Mahatma Gandhi, it still sounded like a good bet to woo Academy voters who like things that are supposed to be good for them, especially things about their industry.

But Chaplin turned out to be something of a commercial and critical disappointment at the time. Thirty years later, the drubbing seems unwarranted. While prone to some of the ponderousness that can bog down high-minded biopics, Chaplin remains a quasi-treat for movie buffs who are likely to eat up the backstories surrounding one of Hollywood’s most enduring legends. And it didn’t hurt that Robert Downey Jr. gave a blockbuster performance as Chaplin.

The movie does not lack ambition. Based on David Robinson’s biography, Chaplin: His Life and Art, as well as the silent-film star’s autobiography, the pictire drifts from the Little Tramp’s impoverished London childhood to his earning an Oscar for lifetime achievement in 1972. Along the way, the picture depicts it all, particularly his comic genius, his leftwing politics and his predilection for underage women.

It’s a sizable narrative undertaking fraught with stumbles. Even with a generous running time of two hours and 20 minutes, Chaplin often feels as if too many events are being shoehorned into place. To help ease things, the screenwriting trio of William Boyd, Bryan Forbes and William Goldman employs a somewhat clunky framing device, having an elderly Chaplin narrate his tale to a fictitious biographer (Anthony Hopkins) at the actor’s Swiss mansion in 1963. The approach lets the filmmakers spoon-feed dribbles of information as they see fit.

The flick’s expansive canvas can overwhelm emotional resonance. As Chaplin’s biographer, Hopkins urges his subject, “You shouldn’t be afraid to let the readers share your emotions, your feelings,” but the same advice could be given to Chaplin the movie. The surfeit of plot isn’t a fatal flaw, but it compromises the poignancy of some story threads, such as Charlie’s mentally ill mother (Geraldine Chaplin) and his ill-fated romance with Paulette Goddard (Diane Lane).

Still, if Chaplin is too big and unwieldy for its own good, it is never less than watchable. Attenborough gussies up the proceedings with the trappings of silent cinema, including wipes and irising, with ace cinematographer Sven Nykvist providing some sumptuous visuals. And there are inspired flashes throughout.

Much of that inspiration can be attributed to Downey, who rightly earned an Oscar nomination for his performance. Playing a bona fide icon is no easy task, but the actor captures Charlie Chaplin’s nimble gifts for physical comedy without resorting to impersonation. He also deftly conveys Chaplin’s fascinating blend of social consciousness and callowness. Chaplin’s real-life daughter, Geraldine Chaplin, marveled at Downey’s portrayal. “I think Daddy took a trip down here and got inside him,” she told an interviewer at the time.

The cast is sprawling and mostly very good. In a nifty bit of stunt casting, Geraldine Chaplin plays her own grandmother, Hannah. Kevin Kline shines as Douglas Fairbanks, while Lane, Moira Kelly, Milla Jovovich, Penelope Ann Miller and Nancy Travis round things out as Chaplin’s various teen love interests. A little tramp, indeed.

One response to “Chaplin (1992)”

Excellent observation. Spot-on!

LikeLike