I wasn’t impressed when I first saw Ghost in the theater back in 1990. At the time, I was a twenty-something cinephile (or movie geek, to be blunt about it) fond of overusing terms like auteur and mise-en-scène, and so I turned my nose up and dismissed the box-office blockbuster as a sappy crowd-pleaser. Now much older and marginally wiser, I will concede to having been wrong about Ghost. Revisiting the movie, I can appreciate the well-oiled craftsmanship that makes this fantasy/romance/thriller hum along. It even endures a leaden performance by Patrick Swayze, may he rest in peace.

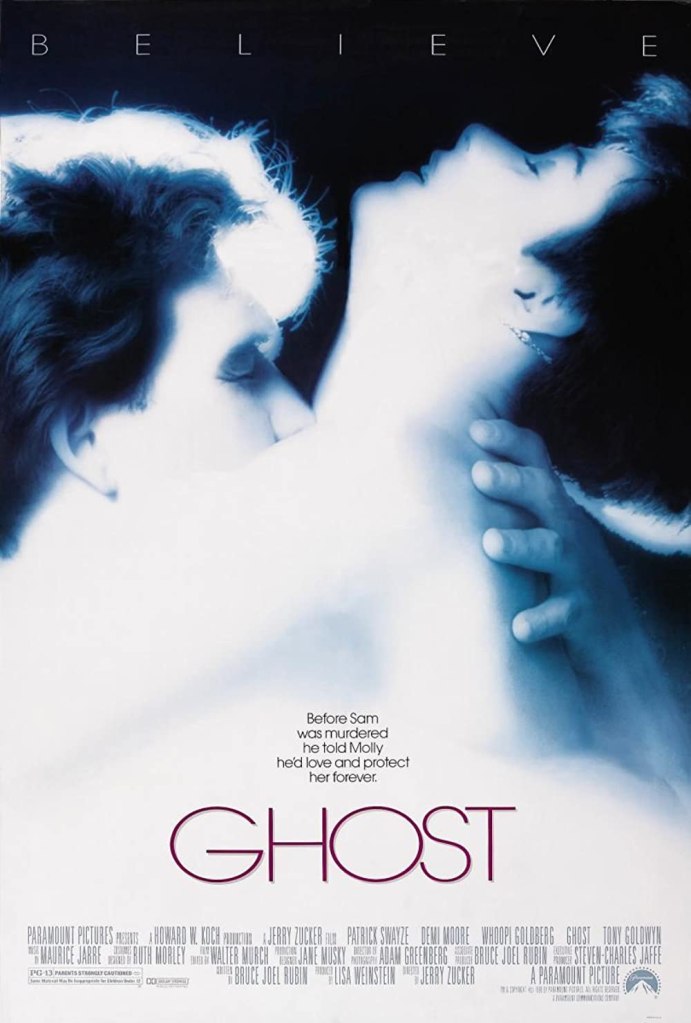

Chances are you know the story. Sam Wheat (Swayze) has a great life. An up-and-coming Wall Street investments consultant, he and his girlfriend, artist Molly Jensen (Demi Moore), live in a spacious, only-in-the-movies New York apartment and have inordinately picturesque sex to the strains of The Righteous Brothers‘ “Unchained Melody.” But then Sam makes the mistake of investigating a mysteriously full account at his bank. That same night, he is shot by a mugger outside a theater and dies in Molly’s arms.

Enter the ghost portion of Ghost. Sam is now a ghost with nothing to do but hang out and observe his grieving love. Over the course of time, he discovers that his murder was engineered by a slimy friend and coworker (Tony Goldwyn) to cover up an elaborate money-laundering scheme.

Moreover, Sam learns that Molly is in danger. Desperate to warn her, our hapless spook enlists the help of a charlatan — and altogether reluctant — psychic, Oda Mae Brown (Whoopi Goldberg).

Despite the movie’s huge box-office success, or perhaps because of it, Ghost was always an easy target for ridicule. It is shamelessly commercial and defiantly schmaltzy. Director Jerry Zucker, one-third of the team that concocted Airplane! and The Naked Gun franchise, brings a light touch to these proceedings. And yet the movie is disciplined, clever and enormously entertaining. Bruce Joel Rubin‘s Oscar-winning screenplay sticks to the rules of the universe it creates, a rare feat in pictures with a paranormal bent.

The filmmakers also deserve credit for their willingness to push dramatic boundaries that risk lapsing into absurdity. The “Unchained Melody” scene, in which Sam and Molly discover the joys of sex ‘n’ pottery, is justly famous – but it practically begs for parody (Zucker himself would spoof Ghost‘s most celebrated scene for The Naked Gun) Similarly, the picture’s climactic ending, juiced by Maurice Jarre‘s swelling musical score, is about as mawkish as they come. But it’s delivered with such sincerity and heart, especially by Moore, that it works.

Another prime example of dramatic risk occurs when Sam temporarily inhabits Oda Mae’s body so that Sam can experience a final moment of intimacy with Molly. Zucker begins with a shot of Oda Mae lovingly caressing Molly’s hands. The director then cuts to show Sam, not Oda Mae, embracing Molly. Although some critics at the time derided the Whoopi/Patrick switch as a sort of compromise, the filmmakers’ decision makes sense within the context of the scene. After all, it is Sam, and not Oda Mae, who reaches out to Molly one last time.

Goldberg won the Best Supporting Actress Oscar for Ghost, but the film benefits from several strong performances. Moore, who spends much of her onscreen time wiping away big tears, is affectingly vulnerable. Goldwyn makes a wonderfully petulant villain, while character-actor extraordinaire Vincent Schiavelli gives a great turn as a belligerent subway apparition.

One response to “Ghost (1990)”

[…] 21. Ghost (1990) […]

LikeLike