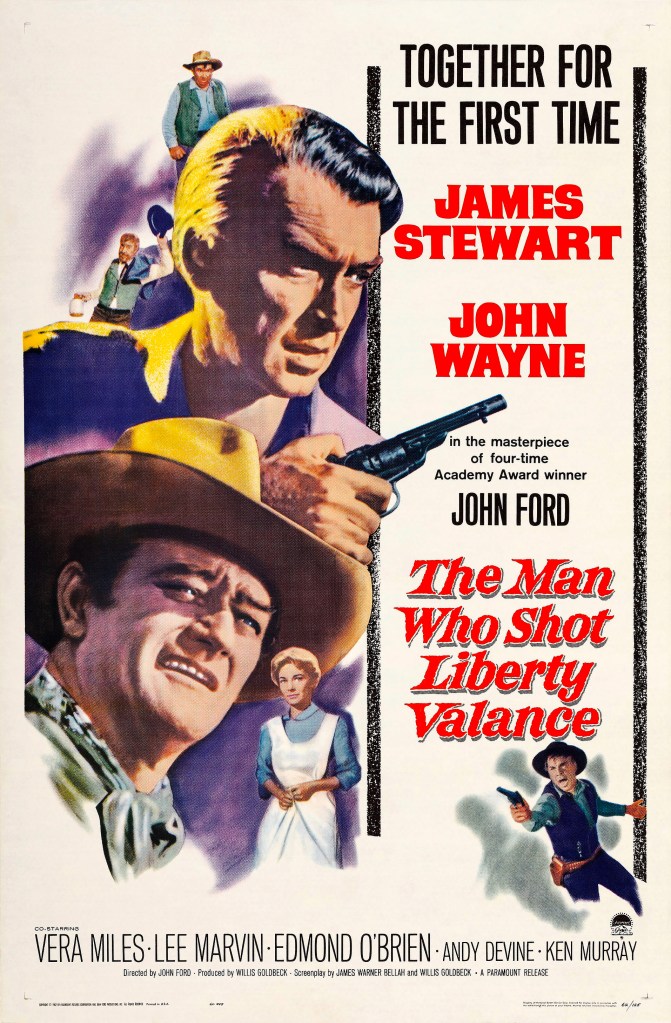

Among the final pictures by John Ford, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance reveals the legendary filmmaker poking a stick at the Old West mythologies he helped create. It’s one of the director’s best, and that’s saying something for the guy who gave us Stagecoach, The Grapes of Wrath, My Darling Clementine, How Green Was My Valley and The Searchers.

Liberty Valance, in form and content, is unmistakably a Ford Western, exploring the tensions between the rugged individualism of the West and its inevitable transformation into orderly society. But the film’s elegiac tone is darker and sadder than most works in the director’s canon. In The Western Films of John Ford, author J.A. Place calls it Ford’s “clearest expression of the current of nostalgia and regret that runs through his work, isolated in this film from the compensating forces of the grandeur of the outdoors and the purifying effect of Ford’s visual beauty.”

To be sure, Liberty Valance is a long way from the majestic landscapes of Ford’s beloved Monument Valley. Shot in black-and-white and largely on soundstages, it is literally and figuratively framed by the death of the West. In this case, that era is embodied by John Wayne‘s Tom Doniphon, whose funeral opens the movie and prompts the lengthy flashback that comprises the bulk of the story.

Aging U.S. Sen. Ransom Stoddard (James Stewart) and his wife, Hallie (Vera Miles), return to the small town of Shinbone to bury their old friend Tom, who has died a pauper. Stoddard, or “Ranse” as he is affectionately known, is cornered by a nosy newspaper editor demanding to know why the august senator would come all the way to this godforsaken town to pay his respects to a forgotten drunk. What unfolds is Ranse’s recounting of how he came to know Tom and how the men’s fates became inexorably linked.

Through flashback, we see Ransom as a young lawyer who has the misfortune of being on a stagecoach robbed by vicious baddie Liberty Valance (Lee Marvin in a star-making role) and his thugs. The idealistic attorney comes to the defense of a fellow passenger and is consequently the recipient of a savage whipping by Liberty.

Ranse is eventually found and saved by Tom and his trusty sidekick, Pompei (Woody Strode). The attorney remains in Shinbone, albeit not to practice law. Instead, he waits tables at the local restaurant and later goes to work for the boozy newspaper editor (Edmond O’Brien, channeling the soused spirit of Ford regular Thomas Mitchell). A love triangle develops, in a fashion, when Ranse becomes friendly with Tom’s would-be sweetheart, Hallie.

But Liberty Valance continues to terrorize the region with his brand of lawlessness. The cowardly town marshal (Andy Devine) is no help. On a more abstract level, civilization’s potential responses to Liberty Valance are neatly encapsulated by Ranse, the law-abiding intellectual; and tough-as-nails Tom, who tells the tenderfoot newcomer that the only force of law that matters in these parts is supplied by a gun. The film’s title makes it clear that Liberty’s eventual comeuppance is no spoiler, but John Ford’s response to the titular mystery is hardly straightforward.

Despite having made an impressive number of bona fide classics, Ford’s critical reputation has dimmed somewhat over the decades as a result of his right-wing politics and embrace of outdated traditionalism. Certainly, it is tough to appreciate the alleged comic relief in The Searchers when Jeffrey Hunter abuses his American Indian wife. Similarly, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance has drawn criticism over the years. The Tom-vs.-Ranse dynamic is surely weighted in favor of the gun-toting cowboy, while book-smart Ranse is subjected to the humiliation of wearing an apron and waiting on tables (evidently taboos in the Old West). Of course, the tale ultimately backs up the contention by Tom Doniphon and Liberty Valance that judicial law is no match for a bullet. SPOILER ALERT (skip to next paragraph if you’ve not seen the movie) “Nobody fights my battles!” Ranse sputters to Tom at one point, but, of course, the attorney owes his life to Tom’s shadow offense.

Liberty Valance is a fascinating and touching portrait of the debate between diplomacy and violence. Ford and his screenwriting team of James Warner Bellah and Willis Goldbeck offer shadings to the partnership/rivalry of the principal characters. The movie delves into a past rife with complexities. SPOILER ALERT (skip to paragraph after next to avoid revelation of key plot points). Ranse Stoddard builds a storied political career on an act of violence that is completely antithetical to his value system — not to mention something for which he falsely accepts credit. Meanwhile, Tom breaks his own moral code by taking a sniper’s shot at Liberty Valance. In so doing, he saves the life of his romantic rival and effectively destroys his future happiness.

Ironies outnumber tumbleweeds here. A bittersweet meditation on the death of the West, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance paradoxically suggests that the romanticism of that bygone time largely stems from falsehoods. “This is the West, sir,” the newspaper editor tells Ranse after the senator has revealed the truth of his ascendance to power. “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” Maybe so, but the movie’s ending scene hints at the guilt, sorrow and loss that haunt the Stoddards.

Perhaps one of the film’s unintentional ambivalences is its casting. Jimmy Stewart was 54 years old when the picture was made, making his portrayal of a young twenty-something more than a bit of a stretch (Peter Bogdanovich posited that Stewart’s old-age and young-age makeup is likely why Ford made an 11th-hour decision to film in black and white). Similarly, Wayne was 55. The casting might have been curious, but The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance likely wouldn’t have been made without the Duke’s star power. Age aside, both are terrific.

One response to “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962)”

[…] Penn4. Lawrence of Arabia, director: David Lean3. The Exterminating Angel, director: Luis Buñuel2. The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, director: John Ford1. The Manchurian Candidate, director: John […]

LikeLike