You have to laugh to keep from crying, the saying goes, but black comedies give us the luxury of doing both. Gallows humor isn’t solely a coping mechanism. Laughter can be empowering. Moreover, by nudging the comic possibilities of the tragic and the taboo, purveyors of dark comedy don’t conceal uncomfortable truths––they expose them. Below are my picks for the 10 best black comedies:

10. The Quiet Family (1998, dir: Kim Jee-woon)

As anyone who ever saw the TV sitcom Newhart can attest, running a rural lodge is no picnic. But the occupational hazards posed by The Quiet Family seem fairly formidable, to say nothing of murderous. A supremely dysfunctional family opens a lodge along a mountain-hiking trail, but misfortune hits when their first guest dies under mysterious circumstances. Trying to keep that death under wraps spurs additional loss of life, and on it goes. South Korean writer-director Kim Jee-woon, who would later explore even darker obsessions in such chillers as A Tale of Two Sisters and I Saw the Devil, keeps the proceedings grimly hilarious.

9. World’s Greatest Dad (2009, Bobcat Goldthwait)

Robin Williams portrays Lance Clayton, an unassuming single father whose 15-year-old son Kyle, a psychopath in the making played by Daryl Sabara, dies from autoerotic asphyxiation gone awry. To cover up the actual cause of death, Lance stages a suicide for Kyle and forges a suicide note. The note later goes viral, making Kyle more popular and interesting in death than he ever was in life. Lance, a high school English teacher and wannabe writer, commodifies his grief by doing more ghostwriting for the not-so-dearly departed. Writer-director Bobcat Goldthwait knows his way around dark comedy. His oeuvre also includes 2006’s Sleeping Dogs Lie, in which a woman admits to her boyfriend that she once blew a dog when she was drunk in college.

8. Welcome to the Dollhouse (1995, dir: Todd Solondz)

On the offhand chance you desire to reopen any psychological scarring from middle school, Todd Solondz bestowed upon the world this comedy so unrelentingly pitch-black that it might require a nightlight. Heather Matarazzo is Dawn, a bespectacled 12-year-old girl who is the verbal punching bag for her class at Benjamin Franklin Jr. High. This modest indie caused a sensation at the 1995 Sundance Film Festival, and it is easy to see why. Solondz’s singular comedy borders on (and occasionally crosses over into) cruelty. Three years later, the writer-director delivered a film (see #2) that would make Welcome to the Dollhouse look like Chitty Chitty Bang Bang by comparison.

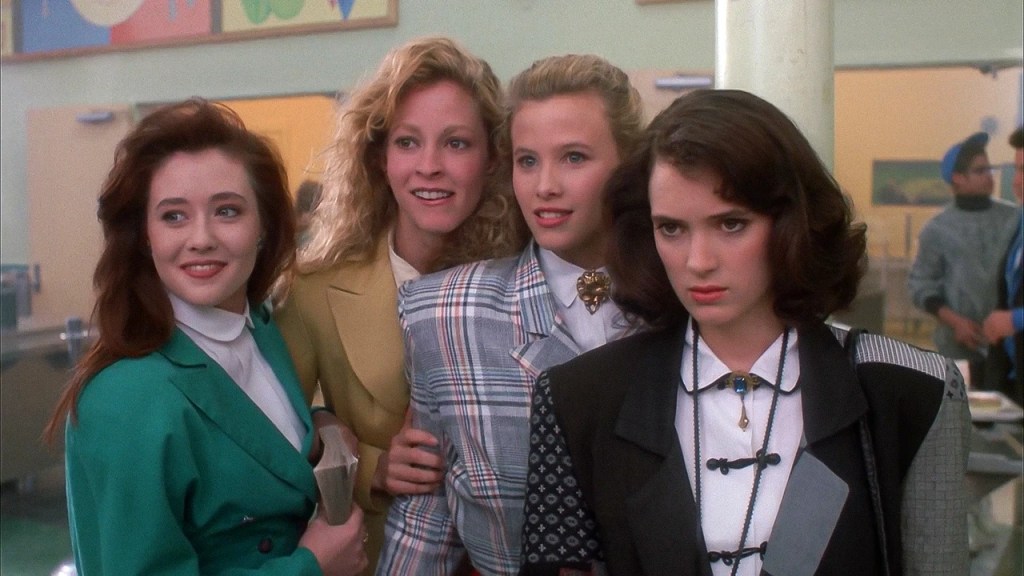

7. Heathers (1988, dir: Michael Lehman)

If you can handle teen suicide as suitable subject matter for a black comedy, have we got a movie for you. As the flip (and dark) side of John Hughes’ teen flicks of the 1980s, Heathers draws blood by slicing and dicing the unforgiving social hierarchies of high school. It imagines how tensions between popular kids and pariahs can lead to murder, a conceit that once seemed ripe for lampooning long before school shootings became tragically commonplace. Starring Winona Ryder and Christian Slater as homicidal teenagers in love, Heathers is a fusillade of razor-sharp dialogue and plot twists. To create a timelessness to his tale, screenwriter Daniel Waters invented teen colloquialisms and slang that still resonate, from “swatch dogs and Diet Coke heads” to the ever-popular, “Well, fuck me gently with a chainsaw.”

6. Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949, dir: Robert Hamer)

Even by today’s callous standards of blackheartedness, this dryly funny film––generally considered the first modern dark comedy––from Britain’s legendary Ealing Studios is shockingly, and wickedly, morbid. We meet our narrator and antihero, Louis Mazzini (Dennis Price), on the eve of his execution. In flashback, he explains how his path to inherited royalty necessitated murdering members of the wealthy D’Ascoyne family. Writer-director Robert Hamer and co-writer John Dighton find delicious ways to whack the uppercrust elites. Price is a wonder of persnickety sociopathy, but Kind Hearts and Coronets’ scene stealer is Alec Guinness, who demonstrates his remarkable dexterity in multiple roles as Louis’ victims.

5. After Hours (1985, dir: Martin Scorsese)

Martin Scorsese’s love letter to the New York of the 1980s is dipped in poison, Griffin Dunne is Paul Hackett, an office drone whose chance meeting with a cute woman at a diner spurs a Kafkaesque (overused adjective, but it fits here) urban nightmare trek through SoHo involving suicide, mistaken identity and a vigilante mob. “I just wanted to leave, you know, my apartment, maybe meet a nice girl,” says an exasperated Paul. “And now I’ve got to die for it?” Rosanna Arquette is irresistibly unhinged as the love interest from the diner, but the entire supporting cast––which includes Linda Fiorentino, Teri Garr, Catherine O’Hara and John Heard––is tremendous. Scripted by Joseph Minion while he was a student at New York University film school, After Hours helped rescue the career of Scorsese, then battling a cocaine habit amid a string of commercial disappointments.

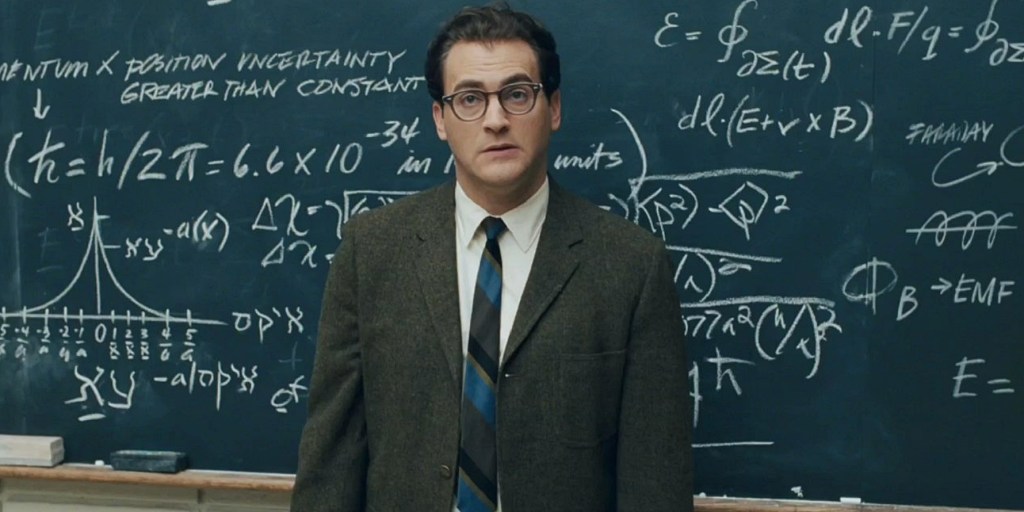

4. A Serious Man (2009, dir: Joel Coen and Ethan Coen)

Joel and Ethan Coens’ recurring preoccupation of human suffering and the seemingly futile search for meaning in the universe are on magnificent display in A Serious Man, arguably the filmmaking brothers’ most personal work. Larry Gopnik (Michael Stuhlbarg), the mild-mannered mensch of A Serious Man, is in a doozy of an existential crisis. His wife is leaving him for another man. He is being financially and psychologically squeezed by self-absorbed children. And just as Larry, who teaches physics at a Minnesota university, is on the cusp of receiving tenure, his colleagues begin receiving anonymous letters that accuse him of awful things. Larry’s increasing desperation leads him to his rabbi. “Why does He make us feel the questions if He’s not going to give us any answers?” asks our protagonist. The answer: “You have to see these things as an expression of God’s will. You don’t have to like it.” (For more anti-cuddly Coen canon, see #1)

3. Dr. Strangelove or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964, dir: Stanley Kubrick)

A comedy about nuclear holocaust at the height of the Cold War? That’s chutzpah. Stanley Kubrick and co-writer Terry Southern based their film on the deadly serious Peter George novel Red Alert, but the pair eventually realized that satirizing global annihilation would be more believable than realism. From the boldly irreverent title to the movie’s preoccupation with sex––an Air Force general orders a strike on the Soviet Union because he blames communism for his impotence––Dr. Strangelove unsparingly skewers the military-industrial complex. It also boasts some of the greatest comic performances of the 1960s, with Sterling Hayden and George C. Scott as pathologically gung-ho military commanders and Peter Sellers is tremendous in a triple role that includes the titular character. The central conceit, that a nation’s leaders would compound a horrific act of aggression by digging themselves in deeper, proved prescient.

2. Happiness (1998, dir: Todd Solondz)

Admittedly, the cringe-inducing black comedies of writer-director Todd Solondz don’t vibe with a lot of moviegoers, which probably speaks to the well-adjusted mental faculties of those anti-fans. A cursory summary of the characters in his magnum opus, Happiness, makes clear why. Dylan Baker delivers an astonishingly ballsy performance as Bill, a married father and successful psychiatrist who also happens to be a self-loathing pedophile. One of his patients, played to skin-crawling perfection by Philip Seymour Hoffman, spends his time masturbating while making obscene phone calls. Among his obscene-call recipients is Joy, played by Jane Adams, a less-than-mediocre folk singer whose main personality trait is patheticness. Solondz somehow wrings a few drops of sympathy for them all, even the sex predators. All this, and a small role for Donald Trump ex-wife Marla Maples! The film threatens to go where you think it cannot possibly go––and then it goes there. Happiness is darkly hilarious, but your laughter is likely to come with a dose of self-reproach.

1. Fargo (1996, dir: Joel Coen)

Filmmaking brothers Joel and Ethan Coen caution the viewer at the beginning of Fargo that it is based on a true story. Don’t believe it. That specious claim is just the first cheeky joke in this flawless tale of duplicity, greed and murder. Set in snowy Minnesota (you are correct in thinking Fargo is in North Dakota), the movie stars William H. Macy in a breakthrough performance as Jerry Lundagaard, a struggling car salesman who arranges to have his wife kidnapped in order to extract $1 million in ransom from his rich but tight-fisted father-in-law (Harve Presnell). Things don’t go as planned. The kidnappers (Steve Buscemi and Peter Stormare) fatally shoot a state trooper and a pair of witnesses. The triple-homicide brings in Sheriff Marge Gunderson, in an Oscar-winning performance by Frances McDormand, whose thick Minnesoter accent and occasional morning sickness belies a sharp investigative mind. From the film’s opening wintry image of a Paul Bunyan statute to climactic use of a wood chipper, Fargo is a masterpiece of misanthropy.

Honorable mention: American Psycho (2000, dir: Mary Harron), Barton Fink (1991, dir: Joel Coen), Catch-22 (1970, dir: Mike Nichols), Election (1999, dir: Alexander Payne), Fight Club (1999, dir: David Fincher), Freeway (1996, dir: Matthew Bright),The Heartbreak Kid (1972, dir: Elaine May), Network (1976, dir: Sidney Lumet), A New Leaf (1971, dir: Elaine May), The Player (1992, dir: Robert Altman)