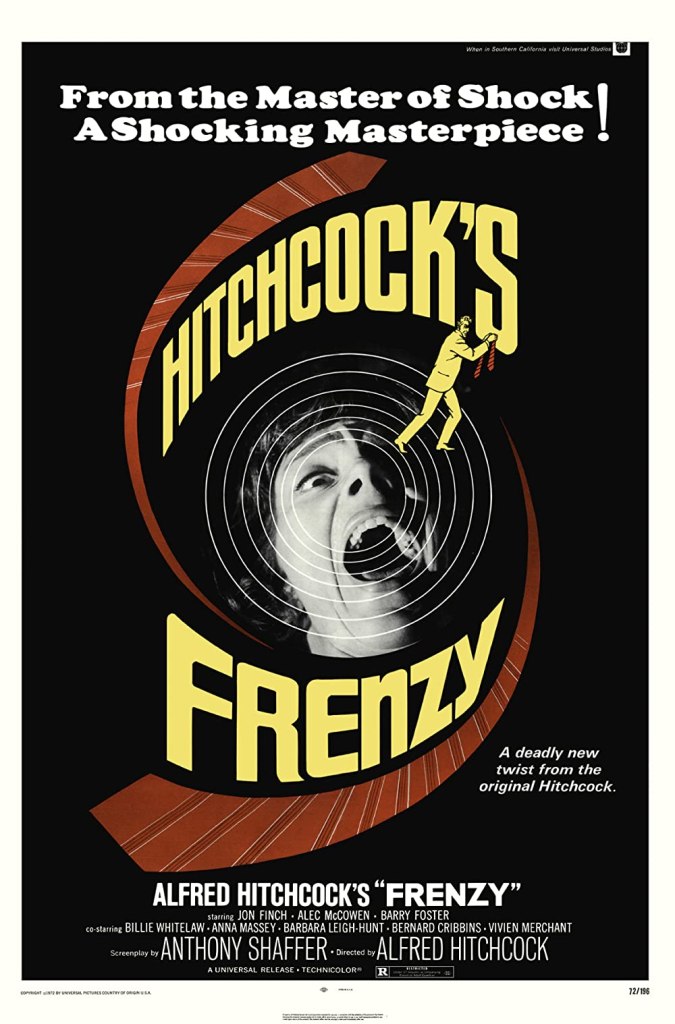

After several disappointments in the 1960s, Frenzy marked a near-return to form for Alfred Hitchcock. It also marked a belated homecoming of sorts for the master of suspense, who returned to his native London for this 1972 thriller that echoed his past glories while simultaneously exploiting the decade’s’ new permissiveness.

Jon Finch stars as Richard “Dick” Blaney, an ex-Royal Air Force squadron leader who has since fallen on hard times. Recently fired from bartending for helping himself to a drink, Dick is penniless and pissed at the world. Perhaps most unfortunate of all, this ill-tempered man is having public meltdowns while London is being terrorized by a serial killer who uses neckties to strangle his female victims.

The so-called “Necktie Murderer,” we soon learn, is none other than Dick’s mate, Bob Rusk (Barry Foster), a friendly produce merchant in Covent Garden. After Rusk rapes and kills Dick’s ex-wife, Brenda Blaney (Barbara Leigh-Hunt) — she runs a matchmaking service that has rejected Bob as a client — circumstantial evidence leads Scotland Yard investigators to suspect Dick as the culprit.

Sound familiar? The legendary filmmaker employed the “wrong man” theme in many of his films (The 39 Steps, Saboteur, North by Northwest, etc.) but few Hitchcock protagonists can match Dick Blaney for sheer unpleasantness. Throughout Frenzy, he has angry tantrums, snipes at whoever happens to be around, and generally feels sorry for himself. There are even hints that he was an abusive husband.

Considerably more likeable, at least on the surface, is affable but murderous Bob Rusk. Indeed, Hitch can’t resist prodding his audience into empathizing with the film’s resident psycho. In the same way that Strangers on a Train’s psychotic Bruno (Robert Walker) strained to retrieve an incriminating cigarette lighter from a gutter, so, too, is Bob Rusk put through agony to recover a tie pin that can identify him as the murderer. In a scene both excruciating and darkly funny, the killer is trapped in the bed of a truck hauling potatoes. He struggles to pry open the fingers of his dead victim while rigor mortis has set in. And we catch ourselves rooting for good ol’ Bob.

That transference of sympathy is particularly unsettling since Frenzy revels in the depravity of Brenda Blaney’s rape and murder. This is brutal stuff, with Hitchcock clearly (gratuitously?) nursing a sadistic streak that had long been stifled by the Hayes Office.

Among Hitchcock’s grimmest works, Frenzy allows free rein for the director’s misogynistic impulses. A police officer, remarking on the Necktie Murderer’s practice of raping his victims before slaying them, jokes to a barmaid that “every cloud has its silver lining.” And that’s a lighter moment.

Most of Frenzy’s comic touches, however, are not so cringey. Hitchcock had a top-notch collaborator in screenwriter Anthony Shaffer. The genius of both men shines in two wonderful scenes that find Scotland Yard’s chief investigator (Alec McCowan) suffering through gourmet meals prepared by his well-meaning wife (Viven Merchant). The scenes not only provide welcome levity, but they also help viewers digest necessary exposition.

Even in Hitchcock’s penultimate film, he continued to experiment with technique. Frenzy boasts several brilliant shots that rank with the director’s best work, but the camera wizardry is always in service to the story. When Bob leads an unsuspecting victim to his flat, the camera follows the pair inside the apartment building but stops as they enter his apartment and Bob shuts the door. The camera then silently backtracks down a staircase and (with the help of a discreet edit) out the building to the bustling street life outside.

In a similar shot, Hitchcock lets the camera linger on the exterior of Brenda Blaney’s office, where we know her secretary (Madge Ryan) will soon discover Brenda’s corpse. The camera is stationary for several beats. Two passersby finally come into frame, and we hear the inevitable scream from inside the building. In both scenes, Hitchcock cleverly conveys the horror behind closed doors.

One response to “Frenzy (1972)”

[…] Michael Ritchie9. The Heartbreak Kid, director: Elaine May8. The Hot Rock, director: Peter Yates7. Frenzy, director: Alfred Hitchcock6. Cries and Whispers, director: Ingmar Bergman5. Sisters, director: […]

LikeLike